Reviving Tradition:

The Returning Activities of overseas Chinese in South China in the 1980s-90s

The interaction between immigrants and their hometowns embodies the circulation of capital and goods, the emotional communication, and the connections in religious culture as well. In South China, the characteristics of the emigrant community gradually emerged and were consolidated with the rise and fall of different port after the mid-19th century. Since then, a large number of overseas immigrants, especially those who migrated to Southeast Asia, maintained close contact with their hometowns in South China. In 1949, after the victory of the Chinese Communist Party, the society of the emigrant community in South China, such as in Chaozhou area, experienced a different social transformation from the past, specifically the transformation of traditional culture. The linkage mechanism between immigrants and their hometowns also changed accordingly. After the reform and opening up in the 1980s, communist China adopted a proactive diplomatic policy toward overseas Chinese. In the local emigrant community, the activity of visiting the ancestral villages became more and more frequently with the donation to construct the infrastructure of those emigrant communities. It cannot be ignored that overseas Chinese had also reconstructed the cultural tradition that had been interrupted for more than 30 years. Taking Hougou village as an example, this article will explore the factors affecting the process of reviving tradition by overseas Chinese.

Keywords: overseas Chinese, South China, emigrant communities, language education, traditional rituals

On the 22nd day of the third lunar month in 1985, the overseas visit group of Hougou Village Association from Thailand arrived in Chenghai county with 144 members. The group planned to worship Tianhou, the goddess, on the following day, which was the birthday of Tianhou. The visiting activities that happened the next day caused a great sensation in the local town. Not only did they worship the goddess Tianhou piously at the Tianhou temple, but also they visited the new building of Hougou Village committee and the waterworks, both of which were built with the help of donations from overseas immigrants from Thailand. Four years later, in 1989, almost the same visit group revisited the village and donated money to rebuild the largest temple in the village——Tenglong Ancient Temple. The tradition of deity parades in Hougou village gradually revived after the ancient temple was repaired.1

In general, in the 1980s, the overseas Chinese from Thailand returned to visit their hometowns frequently, and donated to construct several important infrastructures in their ancestral villages, such as repairing roads, built schools, and improving the welfare of the elderly, which significantly uplifted the material standards of living in these emigrant communities. Moreover, with the further development of reform and opening-up policy in China, various religious activities and traditional cultural rituals had been revived and spread throughout the whole country.2 In the emigrant communities, along with the frequent visiting activities and donations of the overseas Chinese, the cultural living standards of the villagers had been gradually built up. In other words, the frequent interaction between overseas Chinese and their hometowns had a great impact on the material and spiritual-cultural life of the villagers in the 1980s. A large number of overseas donations had the most practical significance in improving the life quality of the villagers. On the other hand, the transnational interaction gradually affected the cultural traditions and customs of the emigrant communities through the reconstruction of temples and practice rituals. Why did the overseas Chinese rebuild the temples in their hometowns? What was the impact on reviving the rural tradition?

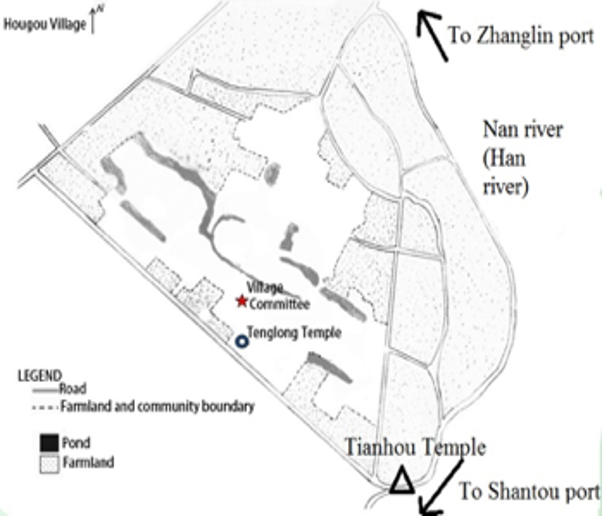

Chaozhou area is located in the east of Guangdong province and the south of Fujian province.3 It has been known as the tail of Guangdong province and the corner of the state due to its unparalleled geographical location. Hougou Village is located in the southeast of Chenghai county, 32 km from the Shantou port, which was opened as a treaty port in 1860. As early as the Ming Dynasty, people from the Chaozhou area maintained close ties with Southeast Asia through the Zhanglin port. With the convenient conditions of Nanxi water transport, Hougou villagers successfully reached Zhanglin port via the downstream of Han River or through the land. At the end of the 19th century, Shantou port replaced Zhanglin port, which was gradually abandoned due to sedimentation.4

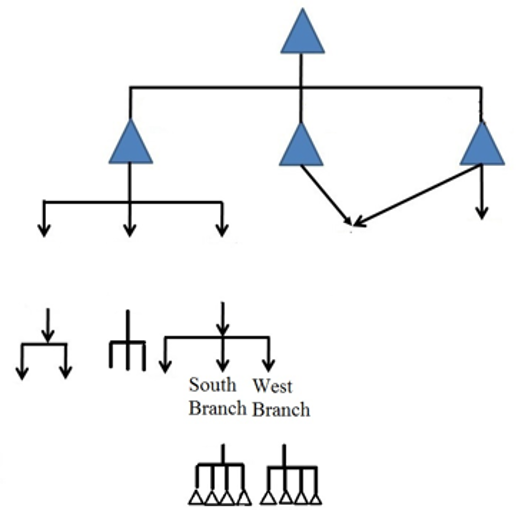

The opening Shantou as a treaty port in 1860 strengthened the connection between Chaozhou Prefecture and the maritime world, and further consolidated the formation of Chaozhou emigrant communities. Migrants from the Chaozhou area, such as Hougou village, were relatively easy to reach the Shantou Port throughout the waterway and then ventured to the Southeast Asian countries to seek better opportunities in the late 19th century and the early of 20th century.5 The transformation and development of the lineage structure of the village had much to do with the migration process at the same time.

In the flow of funds, goods, and personnel, the ocean closely linked the Chaozhou area with Siam, which was one of the most popular destinations of Chaozhou immigrants. Before the Depression happened in the 1930s, the number of Chinese entering Thailand was always higher than that of those leaving Thailand. According to Purcell’s statistics, the number of Chaozhou people living in Siam in 1955 was 1,297,000, accounting for 56% of the Chinese population at the time.6

In the case of Hougou Village, there was no specific data to show how many villagers went abroad, how many of them chose to go to Thailand, or how many of them returned home from overseas. However, from the historical narratives of the villagers, people experienced high mobility through the sea world in several distinct periods. First, as mentioned above, Zhanglin port facilitated the overseas adventure of Hougou villagers since the Ming dynasty. The evidence from the oral interviews showed that Hougou villagers kept a long tradition of worshiping Tianhou before and after landing. Second, after the 1860s, Zhanglin Port was replaced by the newly opened Shantou Port due to sedimentation and other problems.

A growing number of Chaozhou people migrated from Shantou Port. Also benefited from the tributary system of the Han River, Hougou villagers reached Shantou port via the inland river network. One result of the frequent contact with the maritime world emerged in Hougou village was that two branches of Hougou lineage——South branch and West branch——developed into the most powerful two branches with the strongest rural economic strength during this period. The third period was around 1928 after the collapse of the first cooperation between the Kuo- mintang and the Communist Party. Some communists in Hougou village fled overseas due to the failure of political activities, mainly to Thailand; some other villagers chose the same overseas destination to avoid the troubled and complicated situation.7

After the founding of Communist China in 1949, the mobility of the villagers in the emigrant communities in the Chaozhou area was immensely weakened, and few villagers went abroad from the emigrant communities. The social structure of the emigrant communities changed at a rapid rate since the Land Reform initiated in the early 1950s. One of the most noticeable changes in rural society was that the villagers and their overseas relatives were given various labels by different classes. Over the next thirty years, the emigrant communities in the Chaozhou area gradually experienced a process of social transformation from a fluid, mobile maritime environment to an increasingly state-centric agrarian society.8

The rural life in Hougou village in the 1960s and 1970s mainly embraced farming cultivation, such as breeding, plowing, turning, fertilizing, sowing, transplanting, weeding, topdressing, and other agricultural cultivation. The main crops included rice, wheat, sugar cane, peanuts, as well as corn. At the same time, villagers also worked on collecting fertilizers alongside the stream, collecting seafood by the sea, and doing work for brick factories. As the Hougou village was close to the tributaries of the Han River, which was extremely prone to flood disasters, it also required the villagers to improve the soil conditions and build water conservancy during the slack season. Nevertheless, the agricultural production of this emigrant community was difficult to meet the needs of all villagers. Along with the proactive remittance policy of Communist China, the rural life in the emigrant community continued to develop benefited by the inflow of overseas remittance.

In a nutshell, there were three peak migration periods in the history of Hougou Village. After the 1950s, the village plunged into the large-scale agricultural production activity, which was consistent with the overall de- velopment of the emigrant communities in South China.9 Meanwhile, it embodied its own characteristics, which influenced the returning activities of overseas Chinese in the 1980s. In the late Qing Dynasty and the early Republic of China, the water conservancy and traffic conditions of Hougou village in Nanxi river, close to Tianhou temple, had formed a small market for various projects, such as burning bricks, boiling sucrose, shipping, and trading of fishery products. The Tianhou temple had played a crucial role in the flow process of villagers——the last stop to leave the village and the first stop to return home. Therefore, the Tianhou temple naturally became one of the vital places for returning overseas Chinese to worship and donate money for reconstruction in the 1980s. However, the tremendous developments in the village had changed the traditional cultural practices of this emigrant community in the process of social transformation, such as the abandonment of temples, ancestral halls, and other ritual activities. In the 1980s, especially with the implementation of the reform and opening-up policy in mainland China, many overseas Chinese returned home with great enthusiasm and actively donated money to reconstruct their hometowns. Their frequent returning behavior in the 1980s demonstrated a self-imagining of the hometowns, which brought together their common collective memory.

Chaozhou people had a long history of moving to Thailand. By the 20th century, under the extremely complex international political and economic situation, both China and Thailand experienced a series of complicated political movements, war injuries, and economic crises. The ties between the ancestral villages in China and overseas Chinese in Thailand were at risk at any time. The era in which the Phibunsongkhram government was in power in Thailand (1938-1944, 1948-1957) spanned with the period of China’s anti-Japanese War, Civil War, and the establishment of new China. For the villagers with high mobility in the emigrant communities in South China, the complicated political and economic environment at home and abroad made the entry-exit process increasingly difficult, particularly after the founding of new China.

At the beginning of the Cold War, only four countries in Southeast Asia established formal diplomatic rela- tions with mainland China, for instance, Vietnam in 1950, Myanmar in 1950, Indonesia in 1950-1967 and 1990, and Cambodia in 1958. Thailand, as the most popular destina- tion of Chaozhou immigrants, did not establish the official diplomatic relations with China until 1975. The intricate political and economic situations happened from the early days of the Second World War to the establishment of diplomatic relations between China and Thailand had profoundly affected the status of the overseas Chinese living in Thailand.

In Thailand, from the end of the 1930s to the mid-1970s, the Thai government introduced immigration restrictions and limited the newly entered immigrants. At the same time, under the wave of nationalism, Chinese education in Thailand had been strictly constrained. Overseas Chinese living in the host society at least had two main ways of mastering the mother tongue of their ancestral villages, learning from their parents or learning from school education. However, restricting Chinese education had a slow and crossing-generation influence on the language education of Chinese immigrants. Within the visiting group mentioned at the beginning of the article, there was an apparent common feature among them, that was, mastering the language of the ancestral villages, the Chaozhou dialect, or Chinese mandarin.

According to the current research, the development of Chinese education in Thailand experienced the following periods, a slow start period before 1908, a rapid development period from 1908 to 1939, a brief setback period from 1939 to 1945, and a short period of prosperity from 1945 to 1948, a period of declining from 1948 to 1992, and a new period of development from 1992 to the present.10 In other words, the period limiting the development of Chinese education in Thailand was mainly concentrated between 1939-1945 and 1948-1992, especially during the Second World War from 1939 to 1945, and before the establishment of formal diplomatic relations between China and Thailand between 1948 and 1975.

As early as the beginning of the 20th century, Thailand established the rules for Chinese schools. The regulations issued in 1918 stipulated that the overseas Chinese must learn Thai for two or three hours per week, including the history and geography of Thailand. The Thai level of Chinese teachers should be equal to the first and second grades of elementary school. Chinese teachers must take the Thai test after one year of teaching and those who fail will have their teacher qualification canceled. At the beginning of the implementation of the regulations, however, the implementation was not strict to be followed, Chinese schools rarely made a closure. The educational situation had become grave in 1932, for the Thai government listed compulsory education as one of the six major programs of governance after the Revolution happened in Thailand. The compulsory education regulations, initially promulgated in 1921, stipulated that all Chinese children born in Thailand must receive compulsory education and complete the fourth-grade course of Thai elementary School. After the Revolution in 1932, the mandatory regulations were reaffirmed: Chinese children within the forced age must enter a Thai-speaking school, which only had five and a half hours one week to teach Chinese. After that, a new school regulation promulgated by the Thai Government in 1936 emphasized that non-forced classes must also use the Thai language as a medium.11

As mentioned above, the Thai government had already made regulations and restrictions on the Thai language level of Chinese teachers and the Thai learning of Chinese students before the government of Phibunsongkhram. These regulations and restrictions, to a certain extent, limited the inflow of Chinese teachers directly from China without any Thai language background. On the other hand, they ensured that Chinese students could receive Thai education at an early age.

Since August 1, 1939, more than 30 schools were canceled by the Minister of Education, eleven of which were located in Bangkok, due to the failure to comply with the school regulations and of the curriculum design.12 Another report pointed that the government of the Phibun- songkhram closed more than 200 Chinese schools on the grounds of violating the school regulations.13 Although the Thai regime changed in the years after the end of the Second World War, Chinese education had also experienced a brief recovery. For example, on January 23, 1946, the Chinese National Government signed the Sino-Siam Friend- ship Treaty in Bangkok, stating that the Chinese had the freedom to set up schools and educate their children. Nevertheless, soon after the government of Phibunsongkhram regained power in 1948, Chinese education was in trouble again, especially after the “June 15th Incident.”14 By 1950,“Bangkok did not have a Chinese secondary school anymore. Only dusty secondary school sites left such as the Chinese Secondary School affiliated to the Chinese Chamber of Commerce, and Chaozhou Middle School affiliated to Chaozhou Association......those school sites are full of desolate scenes, the spider webs are dusty, the tables, chairs, books, and instruments are still standing there, but are only buried in thick dust.” 15

Concurrent with the Thai government’s restrictions on Chinese education, the Thai government advocated nationalism and rejected the Communist Party’s activities all over the country. Take the example of 390 Thai refugees who arrived in Shantou on November 22, 1953. The report put it that, those refugees included some Chinese workers from “The National People’s Daily,” “Nan Chen Bao,” and “Public Culture Shares Limited,” all of which were illegally closed by the local government, and other Chinese workers, teachers, and merchants, many of whom were arrested by the Thai government on November 10 and December 13 in 1952.16

Until the 1960s, there were still many restrictions on the operation of Chinese schools, although a small number of Chinese schools were functioning normally. According to some reports, Chinese-funded schools only recruited primary school students under the age of four- teen. Chinese students found it challenging to master Chinese due to the limitation of Chinese teaching time. After entering English-Thai-speaking schools, Chinese was quickly abandoned, for English learning became a major and difficult foreign language learning tas. Some Chinese actively embraced the local Thai life, ignored Chinese values and cultures, and abandoned Chinese basic education and thoughts.17 The enthusiasm and extent of Chinese acceptance among Chinese migrants had declined gradually, while Chinese learning and teaching were passively restricted by the Thai government.

The transformation of Chinese education began in the mid and late of the 1960s. Since 1967, the Thai government had allowed universities and secondary schools to offer Chinese courses. “The radio started a Chinese-language radio program to accommodate the needs of three million Chinese living in Thailand.”18 In the 1970s, there had been a wave of learning Chinese in Thailand.19 The newspaper reported that “the number of people who speak Chinese is growing, including drivers, clerks, and waiters etc., and the younger generation is eager to learn Chinese. At the same time, the officially registered Chinese tutoring evening school and the privately-run tutoring classes had been set up.” According to this report, the reasons can be considered from the following four aspects:20

- Since China entered the United Nations, the original status of the Chinese language in the United Nations has been refocused. Chinese is one of the five languages spoken by the United Nations. For the first time in history, the committees must use Chinese, which has led to European and American countries learning Chinese. This sentiment has also spread to Thailand.

- Due to the various changes in the political situation worldwide, Thailand and China have started talking with each other. The current Minister of Industry and Commerce, Prasit Khanchanawat, once the president of the World Journal of Thailand, led a delegation to visit China. Former Foreign Minister Thanat Khoman also took the initiative of the two countries. Establishing formal diplomatic relations between the two countries is just around the corner.

- Although the Thai government has allowed Chinese primary schools to operate until the fourth grade, the recent control of vocational schools (such as the opening of Chinese night classes) has been relaxed. There are about ten Chinese teaching and learning institutes in Bangkok. The number of cram schools is even more numerous.

- Parents from South China have changed their old ideas and actively helped or encouraged their children to learn Chinese.

Coincidentally, the ancestral home of the abovementioned Minister of Industry and Commerce, Prasit Khan- chanawat, was Hougou Village - the special case discussed at the beginning of this article. However, there was little information on whether he kept close ties with the original village. From the implementation of the school regulations in 1918, to the occurrence of “June 15th Incident” in 1948, and the formal establishment of diplomatic relations between China and Thailand in 1975, it can be seen that the most intense period of Chinese education in Thailand should be from 1948 to 1975, especially during the first two decades of this period. During this changeable and long period, one of the most profound influences on the Chinese living in the local area was that there was a lan- guage fault in the Chinese-speaking population. In other words, it was likely that a generation of Chinese migrants would not have a chance to receive systematic Chinese education at school. And then, this long-term and top-down restriction on language education directly affected the educational background of overseas Chinese who would participate in the returning home activity back to the 1980s. In the long run, the education system not only affected those Chinese who are in their sixty or seventy years old today but also the second and third generations of Chinese migrants in Thailand.

After the reform and opening-up policy launched in China, a significant returning peak period of overseas Chinese was formed especially in the 1980s and 1990s, mainly involving the charitable and investing donations from individuals, families, and groups. In Hougou Village, the overseas visiting groups typically consisted of hundreds of members and donated up to one million Thai Baht in many cases, while the personal returning activities were reflected in the donations of funds, large appliances, or as small as teas, tobaccos, and alcohols. In this emigrant community, those basic but important living facilities, such as roads, temples, ancestral halls, and ponds had not been repaired for many years due to lack of funds. Now everything had been improved with the help of overseas contacts and donations. The village office, which was once damaged due to lack of funds, had been converted into a three-story office building with the donation of overseas Chinese. The return of overseas Chinese to the hometowns made the economic and social development of the emigrant community in South China reach a peak of prosperity in the 1980s. The fact that the donations and investments of overseas migrants to the hometowns had obviously improved the material life of their hometowns occurred at different times in South China, such as Man lineage in Hong Kong and Guan lineage in Kaiping.21

In the process of improving the material living conditions in the ancestral village, the overseas Chinese visiting group also chose to donate funds for the religious buildings, such as Tianhou temple. At the same time, they resumed the rural religious activities suspended in the village for 30 years, such as worshipping the Tianhou. One of the most important influences of the returning activities of the overseas Chinese was restoring the traditional culture of the emigrant community. In traditional China, the ritual performance and its recycling had become a means for local elites to integrate into a larger Chinese culture.22 What was the symbolic significance of the practice and restoration of traditional rituals in the emigrant community demonstrated by the returning activities of overseas Chinese? One of the significant commonplaces of the overseas returning group mentioned at the beginning of the article was that the memory of the emigrant community became part of the self-historical memory or part of the family memory. By examining the case of the Ngee Ann Guild in Saigong, Choi Chi Cheung has stated that ethnic identity is constructed through the institution, the symbol, and the collective experience and performance.23 The process to restore the traditional rituals and culture in their hometowns during their visit, to a certain extent, was a reproduction of their collective historical memories and also an enhancement of ethnic identity.

The dominant force in the reproduction of the traditional rituals and culture was the first generation of overseas Chinese, as well as some of the second generation that had close ties with the first generation. The main feature of the first generation of overseas Chinese here was that they owned some experiences living in their hometowns. Their personal memory had a certain degree of overlap with the historical development of the hometowns, and they had a strong feeling of their native homeland. When they returned home after living overseas for a long time, there- fore, there might be a kind of expectation of the reproduction of some historical memory. The second generation of overseas Chinese discussed here, born in the host country, maintained close ties with their ancestral homes, largely because of the influence and traditional education of their parents. When the first generation of overseas Chinese had the ability to return home, their descendants, namely the second generation, were likely to join the returning activity together. Then, the traditional reproduction in the hometowns would play a vital role in the education of traditional cultural and cultural heritage to the next generation. When the scholarships are talking about where the cultural home is in a multicultural society24, the example of Hougou village demonstrates the way in which migrants sought their roots and sense of belonging by reproducing the traditional rituals and culture in their hometowns.

The traditional culture revived by the overseas returnees was part of the life of the ancestral village recognized by overseas Chinese and the process of its integration into the hometowns. Certainly, the tradition was not static, and the process of reviving tradition was selective. The tradition that started to be recovered by overseas Chinese was the worship practice, since it was most relevant to rural life experience and course. In the case of Hougou village, the overseas returnees took the lead in worshipping the Goddess Tianhou, who had the spiritual power to protect those people ventured to Southeast Asia in the old days.

The revival and continuation of the traditional culture in the emigrant communities in the 1980s had a great relationship with the changes of the political and economic environment in both the send and the host countries of overseas migrants. With the accumulation of their life experience in the host country, the returning-hometown requirement of the overseas Chinese was the regeneration of their imaginary traditional culture from the imagination of home and identity. Does the persistence of returning home by overseas Chinese had the meaning of returning to traditional Chinese culture after leaving the motherland for decades?

Based on the example of the migration from Chaozhou to Thailand, it can be seen that in the process of intergenerational change of immigrants, the difference between the first generation and the second-third generation reflected in their mastery of the mother tongue and the language of the host country. The extent of language ability among the different generations of immigrants was an important perspective to explore the adaption process of immigrants to the host society, which was bound to change the emotional distance between immigrants and their ancestral villages. Meanwhile, the economic, social, cultural, and religious changes that happened in the host society would affect the border-crossing and sojourning experiences of immigrants at any time.

Since the end of the 1990s, the emigrant communities in South China had generally faced the problem of alienating from overseas Chinese. The bond maintained by blood and emotion was one of the points for analyzing why the number of overseas Chinese returned was reduced since the late 1990s. In fact, the international economic environment of Southeast Asia, from the late 1990s to the beginning of the twenty-first century, was inseperable from the overall consideration, especially the economic situation of Thailand. On the other hand, the change of generations of immigrants had a profound impact on the links between the ancestral village and the host country.

The complicated transnational migration requires to analyze multiple influential variables.25 The mastery of the mother tongue and the maintenance of historical memory shed more light on the process of understanding the role of overseas Chinese played in the traditional renaissance. From a deeper perspective, the diasporic experience of overseas Chinese is one of the most important factors. Such external factors as restrictions on Chinese education in Thailand, changes of China’s political environment, and the social transformations of emigrant community affect the diasporic experience of overseas Chinese and the generation of their decisions----actively or passively accept. What further needs to be considered is that, under what kind of circumstances overseas immigrants decide to keep in touch with their hometowns, and on what ground they decide to cut off the contact with their hometowns.

1. “[Thai Primary School Education and Civil Education School].” Nanyang Business Daily, September 6, 1962.

2. “[Thailand started the Chinese language boom].” Nanyang Business Daily, February 5, 1973.

3. “[Siam Education I Have Seen].” Nanyang Business Daily, December 24, 1950.

4. “[Thailand begins to learn Chinese].” Nanyang Business Daily, February 5, 1973.

5. “[Thailand Chinese Education].” Nanyang Business Daily, June 26, 1967.

6. “[The Changes of Chinese Education in Thailand].”

Nanyang Business Daily, June 26, 1967.

7. Choi Chi-cheung. ‘Shantou Kaibu yu Haiwai Chaoren Shenfen Rentong de Jiangou: Yi Yuenan Xigong Di’an Shi de Yi’an Huiguan wei Li’ [The Opening of the Shantou Treaty Port and Construction of Identity: A Case Study of the Ngee Ann Guild in Saigong, Vietnam]. in Lee Chee Hiang [Li Zhixian], eds. Haiwai Chaoren de Yimin Jingyan [Migration Experience of the Overseas Chaozhouese]. Singapore: Global Publishing, 2003.

8. Dean, Kenneth. Taoist ritual and popular cults of Southeast China. New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2014.

9. Hong Kong Ta Kung Pao, November 30, 1953.

10. Hougou village Committee. Glorious Footprint: A Brief History of Revolution at Hougou Village, Edited by Xu Xiuying. Chenghai: Hougou Village, 2010.

11. Li Ping. “Study on the History of Thai Chinese Education.” Southeast Asia, August 2012.

12. Liu Shuang. Identity, Hybridity and Cultural home: Chinese Migrants And Diaspora In Multicultural Societies. London and New York: Rowman & Littlefield International, 2015.

13. Munro, Gayle. Transnationalism, Diaspora and Migrants from the former Yugoslavia in Britain. Abingdon: Routledge, 2016.

14. Nanyang Business Daily. August 8, 1939.

15. Purcell, Victor, and Li, Alice. The Chinese in Southeast Asia. London: Oxford University Press, 1965.

16. Shen Ye. The Brightest Moon in Other Homeland: Shen Ye Memoir. Taipei: Du Jia Press, 2003.

17. Siu, Helen F. “Recycling tradition: culture, history, and political economy in the chrysanthemum festivals of South China.” Comparative Studies in Society and History 32, no. 4 (1990): 765-794.

18. Siu, Helen F. Agents and Victims in South China: Accomplices in Rural Revolution. Connecticut: Yale University Press, 1989.

19. The Compilation Committee of the Education Dictionary. Education Dictionary: Overseas Chinese Education, Hong Kong and Macao Education 4. Shanghai: Shanghai Education Press, 1992.

20. The Institute of Asian Studies (IAS). Taiguo Chaozhouren jiqi Guxiang Chaoshan Diqu—Diyiqi Zhanglingang(1767-1850) [Teochiu Chinese in Thailand and in the Native Land at Chaoshan] ชาวจีนแต้จิ๋วในประเทศไทย และในภูมิลำาเนาเดิมที่เฉาซัน สมัยที่หนึ่ง ท่าเรือจางหลิน 2310-2393. Asian Institute of Chulalongkorn University, 1991.

21. Wang Hui, and Xu Xiu-ying. Shantou Ancient Villages: Hougou Village. Guangzhou: Guangdong people’s Publishing House, 2018.

22. Wang Hui. Sojourning and emigration: emigrant communities in Chaoshan area (1949-1958), Social Transformation in Chinese Societies 14, no. 2 (2018): 97-106.

23. Watson, J.L. Emigration and the Chinese Lineage: The Mans in Hong Kong and London. California: University of California Press, 1975.

24. Woon Yuen-fong. Social change and continuity in South China: overseas Chinese and the guan lineage of Kaiping county, 1949-87, The China Quarterly 118 (1989): 327-344.

25. Yen Ching-hwang. “Chaozhou people and fujian people in the early singapore: a comparative study of power structure and power relationship among overseas chinese.” The International Journal of Diasporic Chinese Studies 6, no.1 (2010): 21-50.

26. Zhang Yingqiu. ‘Zhanglin gangkou yu hongtou chuan’ [Zhanglin Port and the Red-head Junks], Shantou Wenshi [Documents and History of Shantou], 8 (1990): 205–215.

All articles/videos are prohibited from reproducing without the permission of the copyright holder.

Welcome to leave a message:

Please Sign In/Sign Up as a member and leave a message