Gentle Waves in the South Seas:

The Story of Singapore Hokkien Huay Kuan

When you visit the Thian Hock Keng (天福宮) at Telok Ayer Street in Singapore to marvel at its majestic façade and religious artefacts, it may be hard to imagine that as early as 1860, it had been the de facto Registry of Marriage for many Chinese couples of Hokkien descent. The couples, however, did not get their marriage certificates from Mazu (媽祖 Goddess of the Sea), the temple's main deity. Instead, the certificates were issued by influential leaders of the Singapore Hokkien Huay Kuan (SHHK) such as Tan Kim Ching (陳金鐘,1829-1892), the elder son of the great philanthropist Tan Tock Seng (陳篤生,1798-1850), and his successors.

You might wonder why SHHK would issue marriage certificates in Thian Hock Keng. The simple answer is that the two had enjoyed a symbiotic relationship since the temple was founded by Tan Tock Seng and other Hokkien community leaders in 1840. They even shared the same birth year. But it was an inconspicuous birth for SHHK, as the locality-based association was housed in a small room of the temple, and the only indication of its existence was a wooden plaque bearing the Chinese inscription 會館 (Huay Kuan). Despite its humble beginnings, SHHK soon became the centre of power for all affairs of the Hokkien community in Singapore, ranging from education and marriage to funeral services. Under the capable stewardship of its early leaders, the wealth and assets of SHHK grew rapidly. Some plots of land that it owned were used to build schools and cemeteries for fellow clansmen.

However, for all its influence and charitable undertakings, SHHK was often seen as playing second fiddle to Thian Hock Keng and had appeared in early records as simply Thian Hock Keng Hokkien Huay Kuan. It was only in 1937 that SHHK became a separate entity, when then chairman Tan Kah Kee registered it as a non-profit organisation under the Companies Act. From then on, the official name of Singapore Hokkien Huay Kuan came into being, and in a reversal of fate, it also took over the management of affiliated schools, cemeteries, and temples including Thian Hock Keng, Kim Lan Beo (金蘭廟, 1830), Goh Chor Tua Pek Kong Temple (梧槽大伯公廟, 1847) and Leng San Teng (麟山亭, 1879).

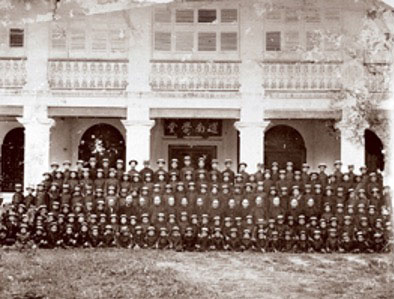

Prior to the statutory change, Tan Kah Kee (陳嘉庚,1874-1961) had introduced reforms to the organisational structure of SHHK in 1929, establishing an executive and a supervisory committee, as well as five departments to take charge of general affairs, economics, education, construction, and welfare respectively. The education department was tasked with overseeing the development of SHHK’s affiliated schools, namely Tao Nan School (道南學校, 1906), Ai Tong School (愛同學校, 1912), Chongfu Primary School (崇福學校, established in 1915 as Chong Hock Girls’ School), and later Nan Chiau High School (南僑中學, established in 1941 as Nan Chiau Teachers’ Training College), Nan Chiau Primary School (南僑小學, 1947), and Kong Hwa School (光華學校, 1953). With their strong emphasis on traditional culture and values, these schools have remained popular choices for parents and students to this day.

After being modernized by Tan Kah Kee, SHHK played an even greater role in helping the Chinese in Singapore as well as in China. It is worth noting that the assistance transcended dialect boundaries and benefitted not just the Hokkien community. During his 20-year tenure as chairman of SHHK (1929-49), Tan Kah Kee spearheaded many social reforms such as eradicating opium-addiction, simplifying religious rituals and shortening funeral duration. He was also instrumental in raising funds for disaster relief, such as in the cases of the Bukit Ho Swee fire (河水山大火) in 1934 (a precursor to the infamous fire of 1961) and severe floods in many parts of China.

When the Sino-Japanese War broke out in 1937, Tan Kah Kee rallied Chinese overseas from around the region to contribute funds and volunteers towards China’s war efforts. On the eve of the Japanese invasion of Singapore in 1942, he also helped the British colonial government to unite the local Chinese in defending Singapore. He led the Singapore Chinese Mobilisation Council which recruited volunteers and labourers in building defence infrastructure, patrolling the streets and clearing bomb sites. His success in these endeavours was due in part to his high standing as the head of SHHK. After the war, Tan Kah Kee resigned from the post and returned to China in 1949. His successor, Tan Lark Sye (陳六使,1897-1972), took over and led SHHK into a transitional period straddling the twilight years of colonial rule and the early years of independence.

Tan Lark Sye is perhaps best-known for his proposal in 1953 to set up Nanyang University (commonly known as Nantah 南大, 1956-1980), the first and only Chinese university established outside China at that time. In support of the effort, SHHK donated 523 acres of land in Jurong to house the campus, and Tan himself also contributed $5 million as seed funding. The fund-raising campaign that followed aroused great fervour among the Chinese community in Singapore and around the region. People from all walks of life including trishaw coolies and nightclub hostesses donated enthusiastically to the effort.

In recognition of SHHK’s contribution to higher education in Singapore, a building in Nanyang Technological University, which occupied the former Nantah campus, was renamed the Singapore Hokkien Huay Kuan Building in October 2019. A road in front of the old Nantah Administration Building (now the Chinese Heritage Centre) was also renamed Tan Lark Sye Walk in honour of its founder. The renaming ceremony was officiated by then Education Minister Ong Ye Kung.

Besides the founding of Nanyang University, Tan Lark Sye’s other accomplishments during his tenure from 1949 to 1972 included the completion of the six-storey SHHK Building in 1955, and negotiations with the government over the exhumation of graves at clan-owned cemeteries and relocating them to Mandai in 1964. In support of newly independent Singapore, SHHK donated 21 acres of land for the establishment of the Singapore Armed Forces Training Institute in 1968 and $300,000 for the setting up of junior colleges in 1970.

Taking over the reins from Tan Lark Sye was banker Wee Cho Yaw, who served for 38 years (1972-2010) and became the longest-serving chairman (renamed president in 1980). During his long tenure, Wee led SHHK on a developmental path largely in line with nation-building efforts to promote social cohesion and racial harmony. Education remained at the core of SHHK’s contributions to the new nation, and vast amounts of financial resources were channelled into its six affiliated schools for expansion, upgrading, and even relocation. Apart from education, it set up the Hokkien Foundation in 1977 to provide financial support for worthy charitable causes in educational, economic, social, and cultural areas. It also launched the SHHK Literary Awards to help nurture local literary talents and the LEAP Awards in recognition of outstanding teachers.

With the adoption of bilingualism in the education system since the 1960s and the launch of the Speak Mandarin Campaign in 1979, the gradual loss of a dialect-speaking environment was a blow to the Chinese clan associations in Singapore. Many small clan associations struggled to adapt to the changes. It was against this backdrop that SHHK and six other major clan associations established the Singapore Federation of Chinese Clan Associations (SFCCA) in 1986 in a bid to pool financial resources and manpower into organising large-scale activities to help preserve Chinese language, culture, and traditions. It has since expanded membership to over 230 associations. Wee Cho Yaw was elected the founding president of SFCCA, while continuing to helm SHHK. As the head of this umbrella organisation, he was able to rally not just the Hokkien clan but also the larger Chinese community to accomplish its mission.

Going into the new millennium, the SHHK constitution was revised to limit the tenure of its president and vice-president to no more than three consecutive terms. The term limit was meant to institutionalise leadership renewal. Wee Cho Yaw stepped down in 2010 under the new constitution and was succeeded by Chua Thian Poh, who also became president of SFCCA. One major accomplishment under Chua was the establishment of the Singapore Hokkien Huay Kuan Cultural Academy at Sennett Road in 2014. It signifies a new milestone in SHHK’s efforts to promote Chinese language and culture by providing bilingual preschool education, afterschool care as well as language, cultural and humanities programmes for all age groups. SHHK also moved its headquarters from Telok Ayer to the Cultural Academy, the first time in 174 years that it had left the city centre.

With globalisation and the rapid rise of China since its reform and opening-up starting in 1978, Chinese clan associations in Singapore have found a renewed purpose in connecting with the outside world. Over the years, many clan associations had organised visits to their native hometowns in China and even hosted “grand reunions” with their overseas counterparts. In 2012, SHHK hosted the 7th World Fujian Convention, an international gathering of Hokkien people from around the world, to great fanfare and success. Unfortunately, the Covid-19 pandemic has halted all such transnational engagements since late 2019. Given the strong kinship ties, however, it can be expected to resume at full throttle when the pandemic is over.

It was in the thick of the global pandemic that SHHK ushered in its 180th anniversary in 2020. Most of the commemorative events had to be either cancelled or scaled down due to pandemic restrictions. As it had done in times of adversity throughout its long history, SHHK rose to the challenge by giving the donations collected for its anniversary to students whose families were affected by the pandemic. Through its charity arm, the Hokkien Foundation, it also donated $1.8 million to the Singapore Institute of Technology (SIT) to support the university’s new campus in the Punggol Digital District.

Thian Hock Keng was given an imperial plaque by Emperor Guangxu in 1907 with the inscription 波靖南溟, comparing it to “the gentle waves in the south seas”. Being an integral part of the temple at the time, SHHK shared the same accolades too. As history has shown, over the span of three centuries, it has played the role of gentle waves in the south seas to ensure the smooth sailing of the boat that is the Chinese community in general, and the Hokkien clan in particular. In times of war and peace, it has proven itself to be a tranquil yet comforting force for the greater good.

Major References

1、Huang, Meiping (黄美萍), Zhong Weiyao (钟伟耀) and Lin Yongmei (林永美), eds. 2007. 新加坡宗乡会馆出版书刊目录 (A Bibliography on the Publications of Singapore Chinese Clan Associations). Singapore: National Library Board.

2、Kwa, Chong Guan and Kua Bak Lim, eds. 2019. A General History of the Chinese in Singapore. Singapore: World Scientific Publishing.

3、Lim, Boon Tan (林文丹) and Peng Cheng Lian (冯清莲), eds. 2005. 新加坡宗乡总会史略 (History of Chinese Clan Associations in Singapore). Singapore: Singapore Federation of Chinese Clan Associations.

4、Toh, Lam Huat (杜南发), ed. 2020. 世纪跨越:新加坡福建会馆180周年报刊史料选汇编 (Transcending Centuries: A Chronicle of Singapore Hokkien Huay Kuan 180 Years of Historical Articles). 2 Volumes. Singapore: Singapore Hokkien Huay Kuan.

All articles/videos are prohibited from reproducing without the permission of the copyright holder.

Welcome to leave a message:

Please Sign In/Sign Up as a member and leave a message