Migration of the Hokkien (Fujian) People to Southeast Asia

Migration of the Hokkien (Fujian) people, mainly from Chiangchew (Zhangzhou漳州) and Chuanchew (Quanzhou泉州) of South Fujian province to Southeast Asia was not a spontaneous act. It was in fact spurred by regular maritime traffic that was well-established since the early 6th century. In the 8th century, Lin Luan (林鑾), a Hokkien merchant from Dongshi (東石), Jinjiang (晉江) led a group of clansmen to Borneo. However, the golden age of Hokkiens’ maritime trade only appeared during the 12th and 13th centuries (Song dynasty), when Chuanchew rose as the most important seaport for China’s foreign trade as well as the most famous ship-building centre in the country. During this period, Hokkien merchants were even more actively engaged in trading at emporia in Southeast Asia, such as Champa, Annam and Java. These three port-polities were most frequented by the Hokkien merchants of the time. With the expansion of maritime trade, Hokkien merchants started to sojourn overseas. For example, in eastern Java, many Hokkien merchants were found settling down among local Javanese and Muslim traders.

The period between 15th and 17th centuries (Ming dynasty) witnessed a substantial increase in Hokkien sojourners in Southeast Asia. Three important events, namely, Zheng He’s seven sea expeditions between 1403 and 1433, the lifting of the ban on private maritime trade in 1567, and the reopening of coastal trade in 1683 under the Qing dynasty brought new level of Chinese movement into and engagement with Southeast Asia. These three events were instrumental in spurring the growth of Hokkien sojourners in Southeast Asia. There were estimates that several hundred junks were involved in the South Seas trade in the 1610s. Manila was one of the Southeast Asian ports most frequented by the Hokkien merchants since the lifting of the Ming ban on Chinese private trade to the south. The junk trade between Fujian and the Philippines in the 1580s involved trading in silks for silver which turned out to be particularly profitable for the Hokkien.

Apart from Manila, Hokkien merchants also patronised other major Southeast Asian ports such as Hoi An (Vietnam), Banten and Batavia (Dutch East Indies, now Indonesia) and Ayutthaya (Siam, now Thailand). They came to these ports not only to conduct entrepot trade but also to establish sojourning mercantile communities. Hoi An had one of the districts along the riverside occupied by Chinese who were mainly Hokkien, amounting to some 4,000 to 5,000 by 1642. Ayutthaya’s entrepôt role that facilitated the exchange of Chinese and Japanese goods for Southeast Asian and Indian ones, was a great magnet for the Hokkien merchants. By 1680s, there were 3,000 to 4,000 Chinese, mostly Hokkien living outside the walled city of Ayutthaya. Banten arose as a major pepper port for the China trade, where Hokkien merchants exported nearly 60% of the pepper produced in the Banten region. They brought vast quantities of silk to barter for silver coins and by the early 1600s, the Hokkien numbered about 3,000 Hokkien, forming the largest group of foreign traders in Banten.

The city of Batavia, which was established by the Dutch East India Company in 1619, was the headquarters of the whole Dutch-Asian trade network. It quickly became another major concentration of Hokkien merchants under the Dutch active encouragement of Chinese immigration. By 1632, there were 2,390 Chinese in Batavia constituting 45% of the free adult male population. The majority were most likely Hokkien since So Bingkong (蘇鳴崗), a Hokkien from Tong An, Fujian, was made Kapitan of the Chinese from 1620 to 1636. Prior to the 18th century, these Hokkien settlements of the Southeast Asian port-polities were primarily trading communities.

primarily trading communities. The growth of China’s economy and the Qing authorities’ relaxation on Chinese coming in and going out of China in the 18th century brought a change that saw the outflow of traders, miners, planters, shipbuilders, mariners and adventurers of all kinds, contributing to the rise of Chinese mining and planting activities in Southeast Asia. This marked a significant shift in the economy of the Hokkien settlements from trade to a mixed economy of trade and primary production. In order to satisfy the market demand for minerals and tropical agricultural products in China and Europe, the port-based Hokkien merchants started to invest in mines and plantations in the interior. Thanks to the Hokkien merchants’ shipping network and capital, the Chinese population experienced unprecedented growth in Southeast Asia in the 18th century. By 1739, Batavia had 14,800 Chinese inhabitants, constituting 17% of the population. In the 1770s, Bangka’s Chinese tin-mining population reached as high as 30,000. The Chinese population of pepper and gambier-planters on the island of Bintan numbered about 25,000 in 1780.

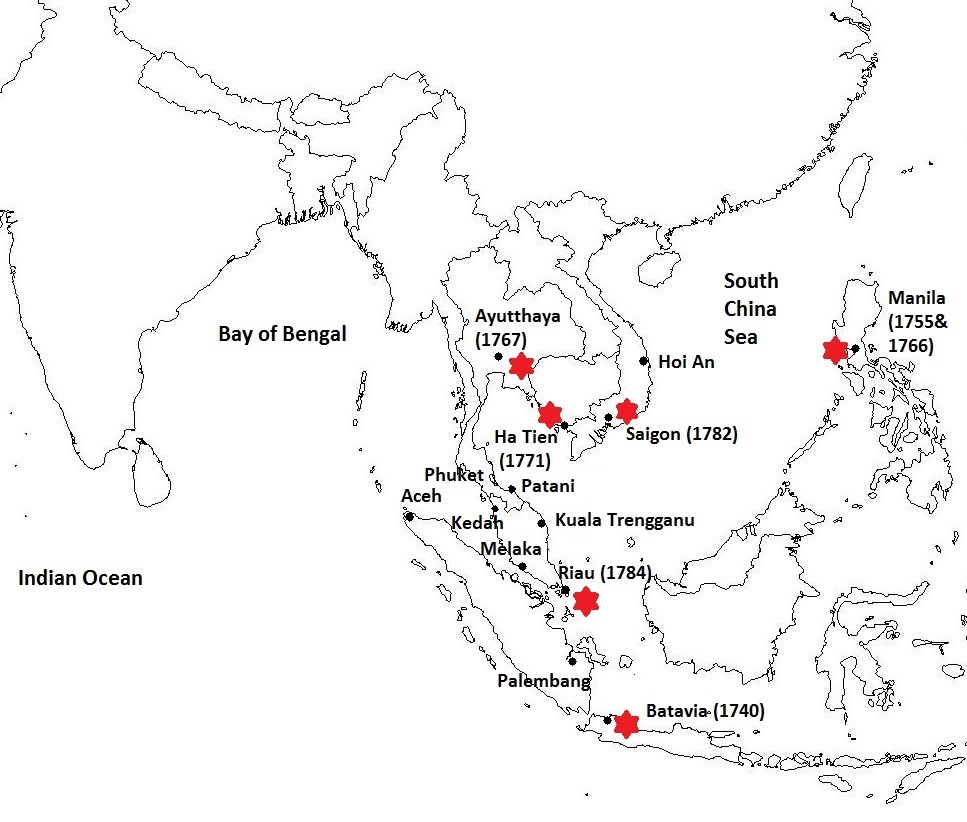

The Hokkien merchants of the time had assumed a formidable economic position on account of their well-developed networks in maritime trade, agriculture and mining industries. It was the Hokkien mercantile networks that crucially developed and sustained the port-polities and coastal hinterlands in Southeast Asia. Nevertheless, a spate of political violence erupted in the port-polities wreaking havoc on certain Chinese settlements: in 1740, the Dutch, who felt their comfortable monopolies threatened by the Chinese, had some 6,000 – 10,000 Chinese in the city of Batavia massacred; in 1755, Spanish concern with Chinese competition prompted the expulsion of all non-Christian Chinese from the Philippines; in 1767, the Burmese launched an attack on Ayutthaya that drove away thousands of Chinese residents; in 1783, Saigon fell to the Tay Son and more than 10,000 Chinese residents were massacred; in 1784, the Dutch, who were envious of and frustrated with the prosperity of Riau, captured the island and put thousands of Chinese to flight. Such relentless political upheaval triggered Chinese migration from major port-polities to minor port-polities, such as Songkhla, Pattani, Terengganu, Kedah, Melaka, Aceh, Padang and Bencoolen dotting southern Siam, the Malay Peninsula and Sumatra in the region.

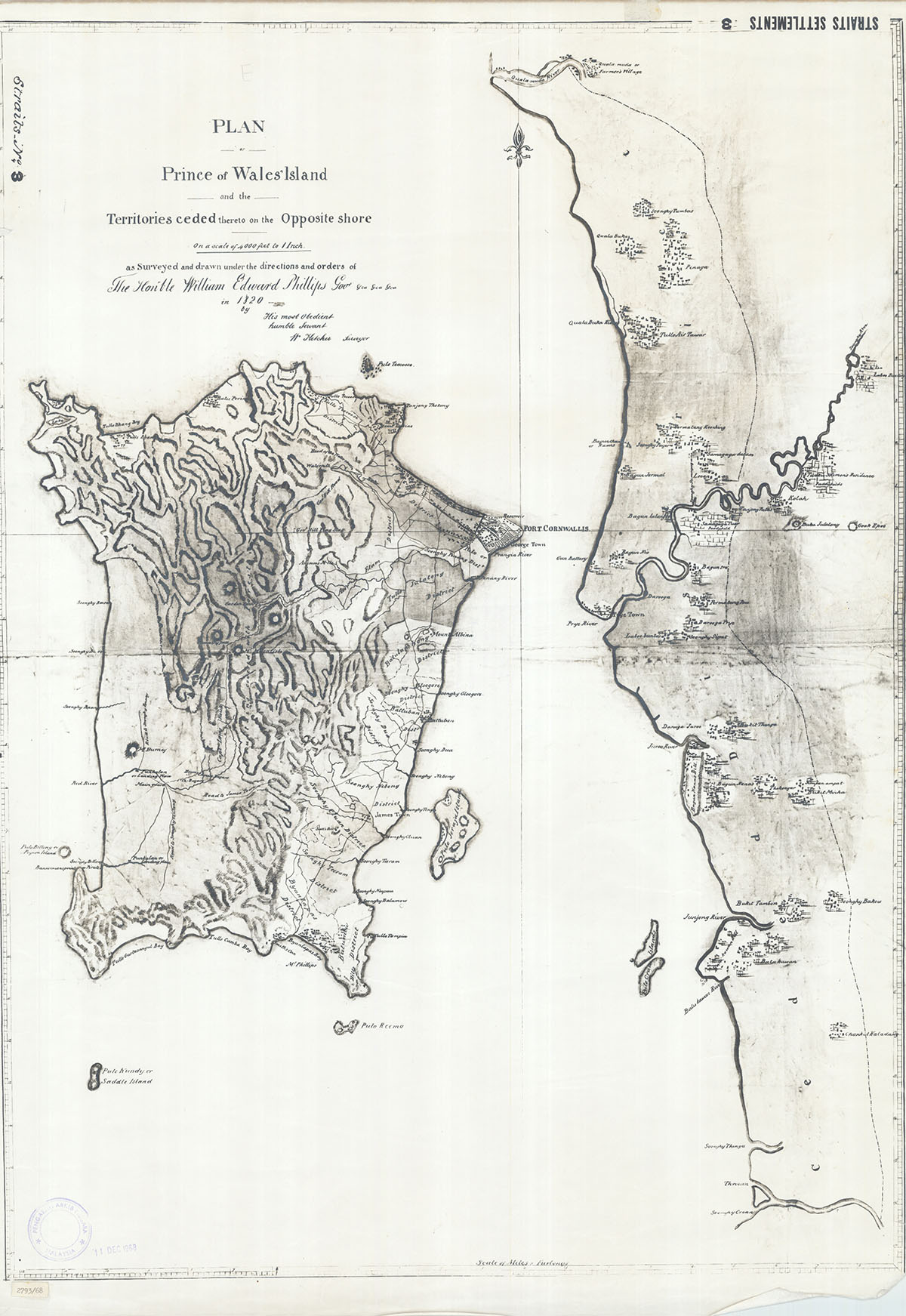

Moving to these minor ports, not all Chinese would settle permanently and some, especially the Hokkien merchants were ready to venture to more promising ports that offered better security and business opportunities. When Penang was established as a trading post by the British in 1786, it attracted Hokkien merchants who were already in the region. For instance, Koh Lay Huan (辜禮歡), the Kapitan China of Kuala Muda, Kedah, moved to the island and settled in George Town. By 1788, there were 405 Chinese inhabitants living in George Town and most of them migrated from Kedah, Songkhla, Pattani, and Melaka. The congregation of Hokkien merchants in George Town played a crucial role in the economy of Penang and the surrounding states. They emerged as the predominant group of the Chinese mercantile community and succeeded in establishing their dominance in the major enterprises such as shipping, trade, planting, tin mining, and opium revenue farms, which generated colossal profits.

Having accumulated their capital, the Hokkien merchants established their respective clan associations in Penang. Among the clan associations, the Khoo Seh Leong San Tong (邱氏龍山堂Khoo Kongsi), the Cheah Seh Sek Tong Shi Teik Tong (謝氏石塘世德堂Cheah Kongsi), the Yeoh Seh Sit Teik Tong (楊氏植德堂Yeoh Kongsi), the Lim Seh Kiu Leong Tong (林氏九龍堂Lim Kongsi), and the Tan Seh Eng Chuan Tong (陳氏潁川堂Tan Kongsi) were the largest and grandest in Malaya, perhaps in Southeast Asia. These five clan associations also had branches in Rangoon (Myanmar) and Phuket (Thailand). One of the major functions of these clan associations was to help destitute clansmen. The clan associations’ material support for immigrants was imperative in time of sickness, unemployment, and death. Because of such needs, these five clan associations had incorporated welfare obligations to clansmen in their rules and by-laws. For instance, Lim Kongsi stated in its by-laws that “the Kongsi may, wherever possible, render pecuniary assistance to any clansmen who is unable to earn his living in consequence of destitution, or sickness. Such clansman may, if he desires, be repatriated to China at the expense of the Kongsi.”

Another function of the clan association was to provide education for the children of members irrespective of their social and economic backgrounds. Education had been highly revered in traditional Chinese society. The first clan school established in Penang was the Sin Kang School (新江學校) founded by the Khoo Kongsi in 1907. This was soon followed by other clan associations in Penang: Lim Double-Grade Clan School (林氏兩等學堂) by the Lim Kongsi in 1908, the Yeoh Kongsi’s Sit Teik Tong Yeoh Clan School (植德堂楊氏學校) in 1909, the Tan Kongsi’s Eng Chuan School (潁川學校) in 1911, and the Cheah Kongsi’s Eok Chye School (育才學校) in 1919. Besides, these Hokkien clan associations maintained close relationships with their hometown in Fujian, China. Khoo Kongsi, for instance, donated RM2.5 million to refurbish Cheng Soon Keong (正順宮) temple in Sin Kang (新江) Village, China in 1993. Donations from Penang were also channeled to maintain public facilities, schools, religious rituals and cultural activities in the ancestral village.

The early twentieth century saw the rise of sinkeh (新客also spelt singkeh) in Malaya. Their number reached several hundred thousand. Some fared well in their business pursuits and became prominent capitalists and entrepreneurs. One shining example was Tan Kah Kee, a Hokkien multi-millionaire based in Singapore. Born in Ji Mei (集美) Village, Tong An district, Fujian, Tan, at the age of 17, went to Singapore in 1890 and worked in his father’s firm. Acquiring the valuable assets of business knowledge, reputation and network from his father, he built up a vast and diversified business empire encompassing rubber planting and milling, pineapple planting and milling, rice milling and trading, sawmilling, brick making, real estate and shipping, which generated an enormous fortune. Being a wealthy businessman, Tan was able and willing to contribute immensely to education and charities in Singapore and China. For instance, Amoy University (today known as Xiamen University), which was established in 1921, is the lasting legacy of Tan.

Over the years, there have been quite a number of prominent Hokkien businessmen and philanthropists in Southeast Asia, particularly Malaysia, Singapore and Indonesia. Vincent Tan Chee Yioun (陳志遠), a Malaysia-based tycoon whose ancestral village is in Eng Choon Prefecture (永春縣), Fujian Province, founded Berjaya Group that served as a vehicle for acquiring a wide array of businesses in leisure and gaming, property and construction, hotels and resorts, insurance, investment holdings, food and beverages, telecommunication, and manufacturing. He also works closely with China’s enterprises to jointly develop a third-party lottery market in China and import, distribute, retail and provide after-sale service for China-made light commercial vehicles and passenger van in Malaysia. Vincent Tan is a signatory of the Giving Pledge – a campaign to encourage wealthy people to contribute the majority of their wealth to philanthropic causes.

Wee Cho Yaw (黃祖耀), born in Quemoy (Jinmen 金門), Fujian Province, is a distinguished banker and a prominent leader of the Chinese community in Singapore. He helmed the United Overseas Bank (UOB), the second largest bank in Singapore for six decades. UOB, under Wee’s leadership, expanded its branch network in Singapore and internationally, and further diversified into property development, textiles, shipping, insurance, hotel management, leisure parks, lease financing and merchant banking. With his success and wealth, Wee became a prominent leader of the Hokkien community and presided over the Singapore Hokkien Huay Kuan (SHHK) from 1972 to 2010. By establishing the Hokkien Foundation in 1977, Wee spearheaded the preservation and promotion of Hokkien culture and education. Besides, the Wee Foundation was set up with S$30 million to focus on education and welfare for the underprivileged, promotes the Chinese language and culture, and fosters greater community spirit and social integration.

Building upon their father’s small business, Oei Hwie Tjhong (黃惠忠Robert Budi Harto) and Oei Hwie Siong (黃惠祥Michael Bambang Hartono), whose ancestral home is Panhu (潘湖), Jinjiang (晉江), Fujian Province, created a conglomerate – Djarum Group (針記集團) in 1979 and became the richest men in Indonesia. Djarum Group controls not only the world's third largest maker of clove cigarettes, but also electronics, palm oil, papermaking, banking, shopping malls, hotels and communication towers. Interestingly, most of the wealth of the Oei brothers comes from Bank Central Asia, Indonesia’s largest private bank. In order to achieve a positive impact on Indonesian society as a whole, the Oei brothers established Djarum Foundation to perform Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) through five programs, namely Djarum Community Contribution, Djarum Badminton Scholarship, Djarum Trees for Life, Djarum Scholarship Plus, and Djarum Cultural Appreciation. These five programs aim to bring Indonesia forward by increasing the quality of its human resources and maintaining the sustainability of its natural resources.

In view of these business achievements, it is no exaggeration to say that an economic era driven by the entrepreneurial flair of the Hokkien continues to prevail in Southeast Asia. All in all, the migration of the Hokkien to Southeast Asia, from temporary sojourn to permanent settlement, has exerted profound and far-reaching impacts on the socioeconomic and political landscapes of Southeast Asia.

Major References

1、 Chin, Kong James. ‘Merchants and Other Sojourners: The Hokkien Overseas, 1570-1760’. PhD thesis, University of Hong Kong, 1998.

2、 Leo, Suryadinata. Southeast Asian Personalities of Chinese Descent: A Biographical Dictionary, Singapore: ISEAS Publishing, 2012.

3、Wade, Geoff. China and Southeast Asia: Volume III Southeast Asia and Qing China (from the seventeenth to the eighteenth century). London; New York: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group, 2009.

4、Wang, Gungwu. ‘Merchants without empire: the Hokkien sojourning communities.’ In The Rise of Merchant Empires: Long Distance Trade in the Early Modern World 1350-1750, edited by James D. Tracy, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990.

5、Wong, Yee Tuan. Penang Chinese Commerce in the 19th Century: The Rise and Fall of the Big Five. Singapore: ISEAS Publishing, 2015.

All articles/videos are prohibited from reproducing without the permission of the copyright holder.

Welcome to leave a message:

Please Sign In/Sign Up as a member and leave a message