Chinese Architecture in Southeast Asia: Hokkien Architecture 福建建築

In Southeast Asia, the association of Chinese architecture with the colour red was primarily due to the region's prevalence of Hokkien religious architecture. This influence is so pervasive that the bulk of Chinese temples in Southeast Asia today are painted in bright red, with little regard for the nuances of regional architectural styles. However, the red in traditional Hokkien architecture is more of a matte earth tone, which is the natural colour of the terracotta floor tiles, fair-faced bricks and terracotta roof tiles used extensively in the architecture, rather than a bright red. Apart from the predominant red colour, the stones used for walls, columns and window fenestrations also contribute to the general colour scheme. There are mainly two types of igneous rocks used in Hokkien architecture: qīngshí (青石), and quánzhōu bái (泉州白), both of which are mined in Fujian province. The former is a fine-grained dark teal stone, produced in Huì’ān county (惠安) and used primarily in round or relief carvings. The latter, a speckled milky white stone is typically used for bas-relief carvings. Another variety of this speckled milky white stone is lóngshí (礱石), which has a tinge of red, giving the stone a soft pinkish hue.

The superstructure of Hokkien architecture is usually topped with terracotta roof tiles, while the gently curved roof ridge terminates on either end with upturned finials resembling the tail of a swallow and is as such referred to as swallowtail ridge (燕尾脊). The roof tiles are supported by timber battens, and the soffit boards are made from timber planks, which are in turn supported by rafters. The rafters are typically painted in red but some have more elaborate paint schemes that mimic timber grain. The timber trusses that support these rafters tend to be polychromatic, while the purlins are usually in shades of red. Similar to the qiàncí (嵌瓷) that is characteristic in Teochew architecture (潮州建築), a version of colourful ceramic shards appliqué ornamentation known as jiǎncí (剪瓷) or jiǎnnián (剪黏) is also seen in Hokkien architecture.

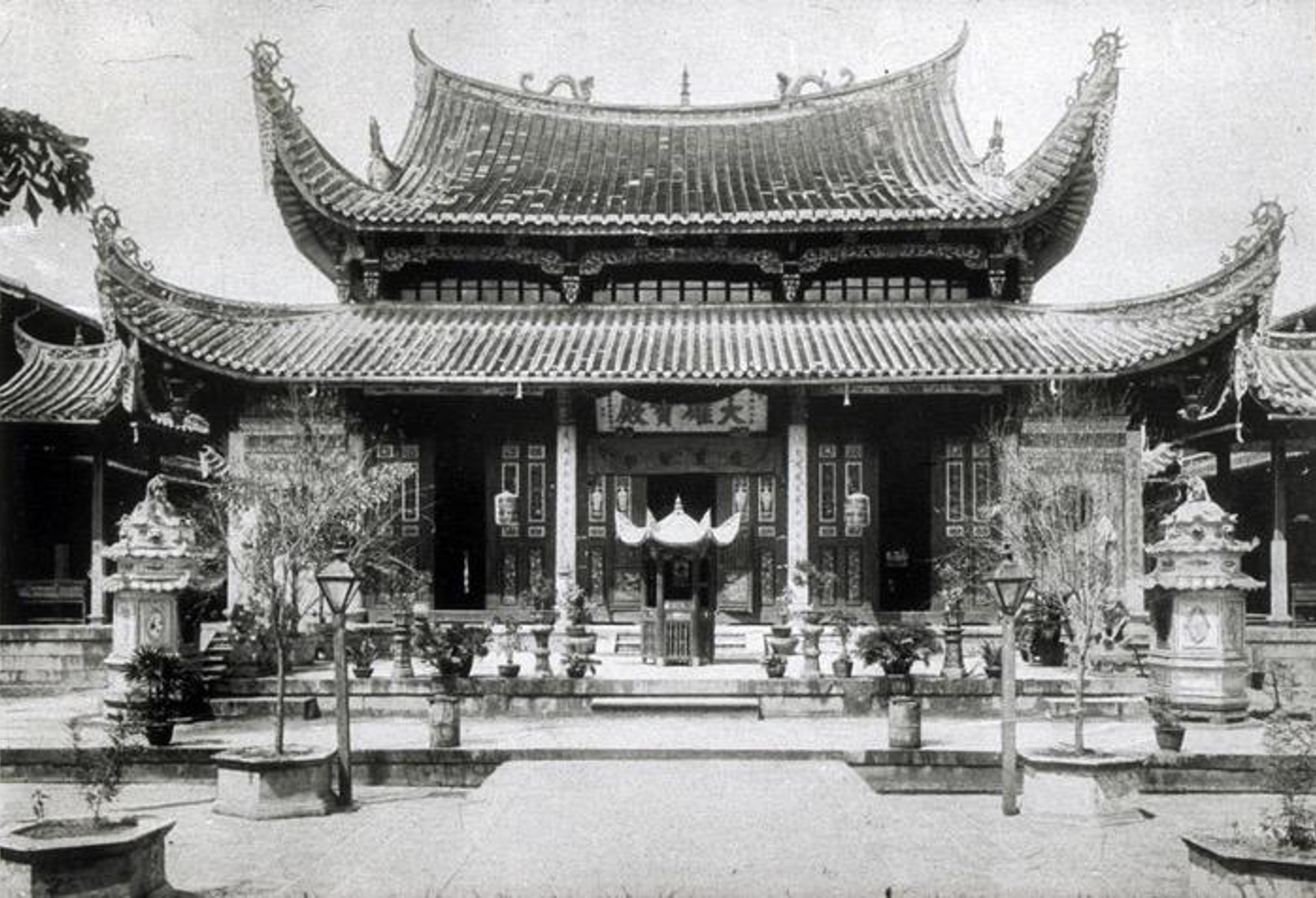

(Leong San Tong Khoo Kongsi, Malaysia)

The vernacular architecture within Fujian province can be further divided into different typologies based on the geographical distributions of the Fujian dialects: Mǐnnán (閩南), Mǐndōng (閩東), Mǐnběi (閩北), Mǐnzhōng (閩中), and Mǐnxī (閩西). With the bulk of migrants originating from Mǐnnán (閩南) and to a certain extent Mǐndōng (閩東), the Hokkien architecture in Southeast Asia can generally be categorised into three typologies: Quánzhōu (泉州) architecture and Zhāngzhōu (漳州) architecture from Mǐnnán; and Fúzhōu (福州) architecture from Mǐndōng. While the differences between Quánzhōu and Zhāngzhōu architecture are slight, the differences between these two typologies from that of Fúzhōu architecture are much greater. In terms of timber components, Quánzhōu architecture tends to be of a more slender proportion than Zhāngzhōu architecture. Another distinctive characteristic of Quánzhōu architecture is the use of Apsara timber cantilever brackets (飛天拱) as part of the roof dǒugǒng (斗拱) system at the entrance hall. Dǒugǒng is an interlocking bracketing system that comprises timber blocks or dǒu (斗), and cantilever brackets or gǒng (拱). In the case of Fúzhōu architecture, its most visible characteristic is undoubtedly the exaggerated upturned roof eaves akin to the soaring wings of birds (《詩經·小雅》: “如鳥斯革,如翚斯飛”).

In Southeast Asia, it is not uncommon to see architectural components of both Quánzhōu and Zhāngzhōu styles used in the same building. The challenge of sourcing for builders and craftsmen from specific traditions within Fujian province also meant that the amalgamation of styles and intermixing across architectural typologies is fairly widespread in Southeast Asia. From the end of the 20th century, more extensive changes were also carried out in traditional buildings, and this was especially so for places of worship. This was due in part to the increased wealth of the Chinese diaspora which financed their endeavours to renovate and embellish these buildings, as well as the advent and availability of modern and supposedly “better” building materials.

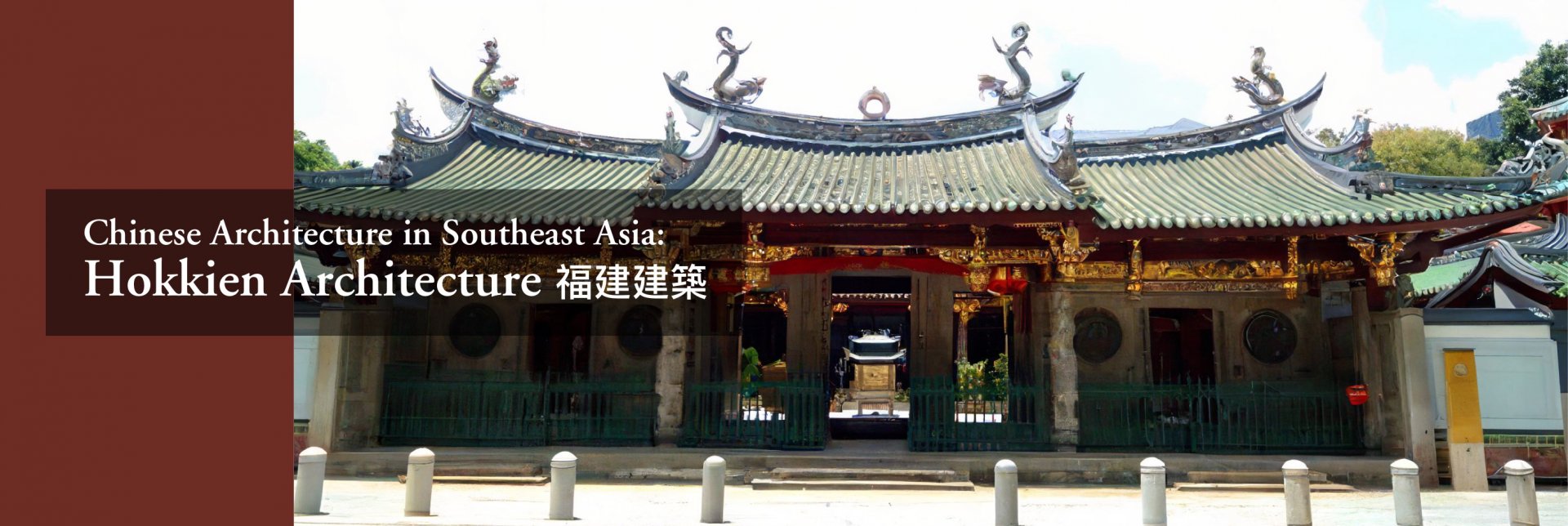

(Thian Hock Keng, Singapore)

For example, stone is typically viewed as a better material compared to fair-faced bricks or plaster. Hence, original adobe brick walls or plastered walls painted in red are often replaced by qīngshí slabs/panels with carvings, thereby changing the architecture's overall colour scheme and visual character. Another trend is to adorn the roof with additional colourful ceramic shards appliqué ornamentation or jiǎncí (剪瓷), which results in a change in the roof’s proportions.

Examples of Hokkien Architecture in Southeast Asia

Malaysia

- Cheng Hoon Teng 青雲亭, Melaka (Quánzhōu architecture)

Cheng Hoon Teng (The Temple of Green Cloud) was founded in the mid-1600s and is acknowledged as one of the oldest Chinese temples in the region. The temple was expanded over time during its long history, with the last major building works carried out in 1801. It is one of the earliest Hokkien temples in the region to undergo restoration and for its efforts, the temple received an Award of Merit at the 2002 UNESCO Asia-Pacific Awards for Cultural Heritage Conservation.

- Leong San Tong Khoo Kongsi 龍山堂邱公司, Penang (Zhāngzhōu architecture)

The current Leong San Tong Khoo Kongsi building was converted between 1902 and 1906 from a bungalow occupied by a clan house. The two-storey structure is a hybrid form that evolved during the colonial era from the Anglo-Malay bungalow on stilts or brick piers. After World War II, the building was restored in 1955 and its latest restoration was in 2001.

The relief carvings featuring stories from the Chinese classics were carved from qīngshí (青石), while the frames that feature bas-relief carvings were quánzhōu bái (泉州白). These two types of igneous rocks are commonly used in Hokkien architecture.

The relief carvings featuring stories from the Chinese classics were carved from qīngshí (青石), while the frames that feature bas-relief carvings were quánzhōu bái (泉州白). These two types of igneous rocks are commonly used in Hokkien architecture.

(Leong San Tong Khoo Kongsi, Malaysia)

- Kek Lok Si 鶴山極樂寺, Penang (Fúzhōu architecture)

Kek Lok Si (Temple of the Land of Paradise) was constructed in 1891 and it is one of the largest Mahayana Buddhism monasteries in the region.

- Thean Kong Thnuah 天公壇, Penang (Fúzhōu architecture)

Thean Kong Thnuah (Temple of the Jade Emperor) was constructed in 1869 specifically for the worship of the Jade Emperor. The temple underwent restoration in 2002.

Singapore

- Thian Hock Keng 天福宮 (Quánzhōu architecture)

Thian Hock Keng (Palace of Heavenly Happiness) is one of Singapore’s oldest Hokkien temples. Built in 1840, it underwent restoration in the late 1990s and received an Honourable Mention in the 2001 UNESCO Asia-Pacific Awards for Cultural Heritage Conservation.

The pumpkin-shaped struts or jīnguā tǒng (金瓜筒) in Quánzhōu architecture (泉州建築) are relatively longer than that of Teochew architecture (潮州建築).

The pumpkin-shaped struts or jīnguā tǒng (金瓜筒) in Quánzhōu architecture (泉州建築) are relatively longer than that of Teochew architecture (潮州建築).

(Thian Hock Keng, Singapore)

- Hong San See 鳳山寺 (Quánzhōu architecture)

The current Hong San See (Temple on Phoenix Hill) was relocated to its current site between 1908 and 1913. Established by a group of Hokkien from the Nán'ān county (南安) of Fujian province, it is dedicated to the deity Guǎngzé Zūnwáng (廣澤尊王). The temple received the Award of Excellence in the 2010 UNESCO Asia-Pacific Heritage Awards for Cultural Heritage Conservation for its conservation efforts.

- Lian Shan Shuang Lin Monastery 蓮山雙林禪寺 (Fúzhōu architecture with Quánzhōu, Zhāngzhōu and Teochew influence)

Lian Shan Shuang Lin Monastery (Twin Grove Monastery on Lotus Hill) is established between 1898 and 1900. Construction started soon after, with most of the structures completed by 1907. It is the oldest Buddhist monastery in Singapore and is known for its Fúzhōu architecture with influences from other typologies.

The exaggerated upturned roof eaves are distinctive of Fúzhōu architecture (福州建築).

The exaggerated upturned roof eaves are distinctive of Fúzhōu architecture (福州建築).

(Lian Shan Shuang Lin Monastery, Singapore)

Thailand

- Kian Un Keng 建安宮, Bangkok (Zhāngzhōu architecture)

Kian Un Keng, also spelt as Kuan An Keng (Temple that builds Peace and Tranquillity), is one of the oldest Hokkien temples in Bangkok. The current building was reconstructed during the reign of King Rama III (1824 – 1851), and in 2008, received the Architectural Conservation Award from the Association of Siamese Architects (ASA) for its restoration efforts.

Indonesia

- Kim Tek Ie (Vihara Dharma Bhakti) 金德院, Jakarta (Zhāngzhōu architecture)

Kim Tek Ie (Temple of Golden Virtue), also known as Vihara Dharma Bhakti, is believed to be established in 1650 and restored in 1755. Unfortunately, the temple was destroyed by fire on 2 March 2015.

The hanging flower struts or chuíhuā tǒng (垂花筒) of this Zhāngzhōu architecture (漳州建築) are rounder compared to those seen in Quánzhōu architecture (泉州建築) which are relatively more slender in proportion. The red ceramic tiles and red enamel paints on the walls were recent additions. Unfortunately, this building was lost to fire in March 2015.

(Kim Tek Ie, Jakarta, Indonesia) - Tay Kak Sie 大覺寺, Semarang (Zhāngzhōu architecture)

Tay Kak Sie (Temple of the Great Enlightenment) is believed to be established in 1746. The temple was expanded and embellished several times throughout its history, with the last major works dating to 1911.

- Kong Tik Soe 功德祠, Semarang (Quánzhōu architecture)三寶壟「功德祠」(泉州建築)

Kong Tik Soe (Temple of Merits) was founded in 1845 and located adjacent to Tay Kak Sie. The building underwent restoration many times with the last major works carried out in 1907. Unfortunately, the building was lost to fire on 21 March 2019.

The presence of Apsara timber cantilever brackets (飛天拱) is indicative of this being Quánzhōu architecture (泉州建築). Its hanging flower strut is also of a more slender proportion compared to that of Zhāngzhōu architecture (漳州建築). This building was unfortunately destroyed by fire in March 2019.

The presence of Apsara timber cantilever brackets (飛天拱) is indicative of this being Quánzhōu architecture (泉州建築). Its hanging flower strut is also of a more slender proportion compared to that of Zhāngzhōu architecture (漳州建築). This building was unfortunately destroyed by fire in March 2019.

(Kong Tik Soe, Semarang, Indonesia)

- Weihui Gong 威惠宮, Semarang (Zhāngzhōu architecture)Weihui Gong (Temple of Majesty and Kindness) is also known as the Ancestral Temple of the Chen (陳) Family. It was founded in 1815 and restored in 1863.

Philippines

- Chong Hock Tong 崇福堂, Manila (originally Quánzhōu architecture)

Chong Hock Tong (Temple of Lofty Happiness) was built in 1878. The temple underwent several additions and alterations, namely the addition of two bell portals flanking the sides of the entrance hall. These portals originally were designed and constructed with European influences but were reconstructed subsequently in the form of Chinese gateways or páilóu (牌樓).

The temple was unfortunately demolished on 15 March 2015. Although it has been reconstructed in 2017, the architectural finishes have been altered.

Hokkien Architecture: Rule of Thumb

-

Exterior colour scheme: Predominantly red (terracotta roof tiles, fair-faced bricks, terracotta floor tiles), with red or white (plastered walls).

-

Roof curvature: Gentle curve; gentle slope (gradient).

-

Roof ornamentation: Ceramic shards appliqué ornamentation or jiǎncí (剪瓷), also known as jiǎnnián (剪黏).

-

Roof fascia board: Plain fascia board painted in red oil-based paints.

-

Exterior façade: Typically with stone window openings.

-

Door frame and pier: Stone door frames are typically paired with qīngshí (青石) stone drums or lions to provide lateral support to the door frame.

-

Timber carving: Relief carving with gold-gilding, lacquer and polychromatic oil-based paints.

Reference:

1. 杜南發 等, 《南海明珠: 天福宮》, 新加坡: 新加坡福建會館, 2010.

2. 阮章魁, 《福州民居營建技術》, 中國: 中國建築工業出版社, 2016.

3. 張玉瑜, 《福建傳統大木匠師技藝研究》, 中國: 東南大學出版社, 2010.

4. 楊莽華, 馬全寶, 姚洪峰, 《閩南民居傳統營造技藝》, 中國: 安徽科學技術出版社, 2013.

5. 蔣若琳, 《臺灣龍柱石雕研究(1895-1945): 以惠安石匠辛阿救為中心》, 台灣: 蘭臺網路, 2021.

6. 鄭慧銘, 《閩南傳統建築裝飾》, 中國: 中國建築工業出版社, 2018.

7. 戴志堅, 《福建民居》, 中國: 中國建築工業出版社, 2009.

8. 戴志堅, 陳琦, 《福建古建築》, 中國: 中國建築工業出版社, 2015.

All articles/videos are prohibited from reproducing without the permission of the copyright holder.

Welcome to leave a message:

Please Sign In/Sign Up as a member and leave a message