The Circulation of Chinese Ink Painting Art in East Asian Communities

Ink Painting Art, which is originated from Chinese traditional painting, becomes one of the symbolic Chinese art forms owing to its unique worldview towards art and extensive cultural upbringing. Chinese traditional painting, which is also called “Dan-qing (丹青)”, was hailed as “National Painting of China (國畫)” in the 20th century due to the rise of nationalism in China. This special art form, which is signified by the use of ink wash or coloured ink on silk fabric or paper, has spread to nearby East Asian communities and other parts of the world alongside with the popularity of Chinese calligraphy in those areas. As both Chinese painting and Chinese calligraphy utilize same tools and materials (using brush to put paints on paper), we do not use the word “draw” (hua, 畫) to describe the process, but use “write” (xie 寫) instead. The prevailing trend of globalization and recent advancement in technology in various parts of the world provide momentum for changes in Chinese painting, allowing artists to breakthrough the limitation of forms and media, thus opening a new phase of versatility in Chinese art.

Chinese painting has two major emphases: resemblance in appearance and essence. In other words, only the painters who are not restricted in exact reproduction of the external appearance, but the painters who can capture the essence by slight variation of the forms, could be regarded as achieving the highest standard in art: extra-ordinary class (Yi-Pin, 逸品, something stands out from ordinary work which could be regarded as others). Hsieh Ho (which is also translated as Xie He, 謝赫, late 4th century AD – early 5th century AD), a famous aesthetic theorist in Southern Qi Dynasty (南齊 479-502) and Southern Liang Dynasty (南梁, 502-557), proposed a famous proposition “Six principles in art” (六法), which included the following: “First, lively expression of essence and aura” (氣韻生動); Second, skilful utilization of brush with force (骨法用筆); Third, similarity with natural objects (應物象形); fourth, vivid usage of colour (隨類賦彩); fifth, arrangement of objects and space (經營位置); and sixth, keep practising by taking reference from classics but injecting the painters’ insights and emotions into it (傳移摹寫). (「六法者何? 一氣韻生動是也,二骨法用筆是也,三應物象形是也,四隨類賦彩是也,五經營位置是也,六傳移模寫是也。」) The most important principle, “lively expression of essence and aura”, emphasizes the realization of inner quality and the flair of elegance. In doing so, the artwork would be appreciated for its vitality and capacity to induce deep emotion, thus becoming an “extra-ordinary class” (Yi-pin, 逸品). Other principles, which deal with external appearance, colour, and general structure of the artwork, are simply the basis of art, therefore are ranked as less important than the first principle.

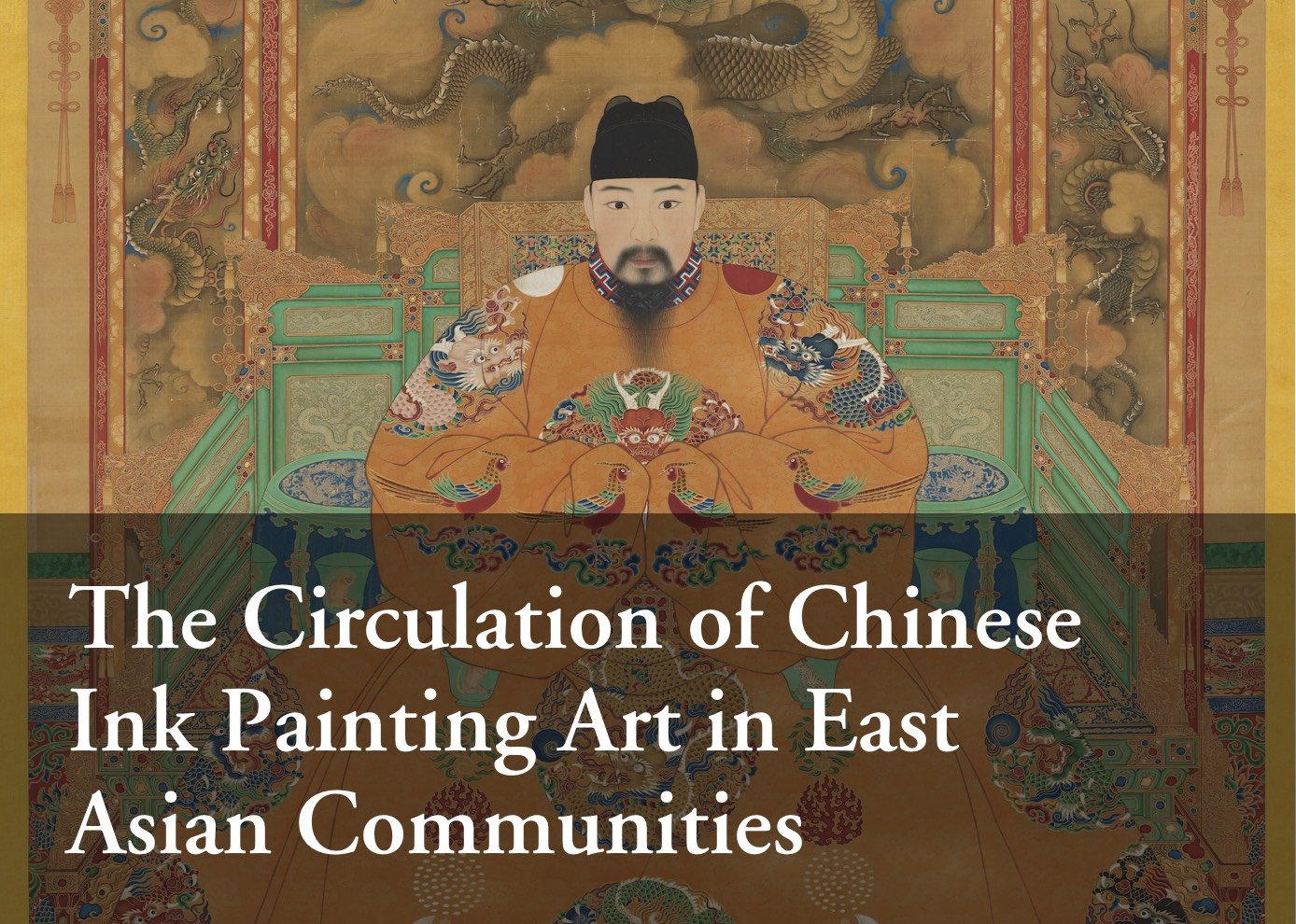

Due to this worldview towards art, Chinese art is different from European portrait paintings, which emphasize the exact representation of one’s appearance. Taking the portrait paintings for Chinese emperors and empresses as examples, even these paintings do not lack fine details and skilful usage of colours, but unlike European portraits, exactness is not the most important criterion of Chinese art. Taking Hong-zhi Emperor in Ming Dynasty (朱祐樘,弘治帝,明孝宗, 1470-1505) as an example (Attached is the portrait of Hong-zhi emperor sitting (Collection in Qing-Dynasty Palace Southxundian 清宮南薰殿舊藏) (Figure 1)). The figure does not perfectly represent stereoscopy and the facial details are not expressed explicitly. Nonetheless, one could feel the solemn eyesight from this picture. There are also numerous ornaments with symbolic representations, for example, the sun and the moon ornaments in the emperor’s shoulders connote light from the sun and the moon, which represent the emperor’s power all over the land. The golden pheasant (錦鷄) on the sleeves connotes special talent in literature; while the axe with protruded patterns represents decisiveness and ability. The icons on the axe, which are rice, fire, and algae respectively from top to bottom, represent peace under the emperor’s ruling, righteous in character, and high moral standard. Therefore, this type of portrait with the emperor or the empresses sitting is not targeting at simple resemblance of facial details, but for expressing the solemn power from the emperor as the person who owns the country.

During the Tang Dynasty (618-907), the nation was strong and solid. Many Buddhist monks from China came to Korea and Japan as missionaries, thus spreading Chinese paintings to these areas. For example, during the heyday of Muromachi period (室町時代,1338-1573), the family of Ashikaga (足利) – the Shogun owned a huge collection of highly acclaimed paintings and calligraphies in the Song (宋), Yuan (元) and later Ming (明) dynasties. The collection is regarded as tool to symbolize the power of the general’s family. On the other hand, Japanese ink painters such as Tensho Shubun (天章周文 1414-1463) (Figure 2), Sesshu Toyo (雪舟等揚 1420-1506) (Figure 3), and Kanō Masanobu (狩野正信 1434-1530) (Figure 4) incorporated Japanese landscapes, national aura, and worldviews into the aesthetics of Chinese ink painting, rendering it a painting style with Japanese characteristic and values.

Thanks to the ever-advancing technology, there is new development of ink paintings in modern times that overcomes the limitation of art media, for example, decorative ink painting, ink painting animation and multi-media ink painting art etc. Korean artist Lee Lee Nam (李二男, born 1969), who is renowned for incorporating multi-media and ink painting art, recently created an multi-media artwork Reborn Light-Songhamang Falls (《重生之光與松下觀瀑》, 2019) (Figure 5). He adopted the work of mandarin artist Kang I-O (姜彛五, 1788- 1857) from late Joseon dynasty (1394-1910) titled Observing Waterfall under Pine Tree (《松下觀瀑》) as the background, having crossover with the signature work from Belgian Surrealism painter René Magritte (1898-1967), Le fils de l'homme (The son of the man, 1964) at the front (see the man wearing the black hat in Lee’s artwork). The on/off of the oil lamp lets audience travel through the past and the present, the East and the West, in time and space. To conclude, Ink Painting signifies the special spirit in culture and beauty of the nature. In the meantime, it has undergone transformation in its art-forms by bearing the changes in history and modernity. of. Therefore, Ink Painting could be regarded as an important intersection among various Asian communities.

Major References

1、李澤厚:《美的歷程》,北京:文物出版社,1981年。

2、薄松年:《中國藝術史》,台北: 聯經出版,2006年。

3、徐小虎:《日本美術史》,南寧:廣西示範大學出版社,2019年。

All articles/videos are prohibited from reproducing without the permission of the copyright holder.

Welcome to leave a message:

Please Sign In/Sign Up as a member and leave a message