Navigating Nanyin in the Nanyang

Nanyin (南音) music, translated as “music from the south”, is a form of ancient Chinese music that traces its historical origins back to the Han Dynasty (206BC – 220AD).1 Played on a range of musical instruments – pipa, dongxiao, erxian, sanxian – a band of performers come together to produce the artform.2 Although known literally as “music from the south”, the origins of Nanyin itself extends far beyond just the southern region of China. For example, various musical elements originating from the Tang and Song Dynasties, as well as the “Western Regions and the Central Plains” of China have been noted by musicologists to be present in Nanyin music. Up till the early 20th century, Nanyin was a mainstream musical tradition of southern Fujian - the "predominant form of daily leisure and self-cultivating activity before the introduction of radio and television" that was also "an important part of communal life-cycle events and temple fairs".3 Connecting their communities (“Hokkien” or “Hoklo”) in southern Fujian with the Chinese diaspora, Nanyin is a sociocultural and musical heritage that changed alongside the diaspora which played and listened to its tunes. In the 21st century, one sees many variations of Nanyin across different countries. This article traces some of these changes among different Chinese communities in Southeast Asia, with an emphasis on Singapore.

Before the rapid changes of the 20th century, Nanyin was customarily performed both in homes and at temples amongst the Hokkien. Its musical spaces were called guan (馆; halls] or ge (阁; pavilions], which could range from unnamed private residences to communal halls. They enjoyed the ritual of tea-making and indulged in Nanyin playing, smoking and chatting, a trend sustained across the decades. In China as in Southeast Asia, changes in Nanyin paralleled the great transformations of their societies. In the context of Chinese nationalism for instance, master Chen Wuding’s (陈武定) song skits condemned the feudal system and its regressive society against the backdrop of a fallen Qing Dynasty.4 Beyond China, Nanyin witnessed and transformed alongside similarly momentous changes that Chinese immigrants experienced in places as diverse as Taiwan, Hong Kong, Indonesia and Singapore. Before the rapid changes of the 20th century, Nanyin was customarily performed both in homes and at temples amongst the Hokkien. Its musical spaces were called guan (馆; halls] or ge (阁; pavilions], which could range from unnamed private residences to communal halls. They enjoyed the ritual of tea-making and indulged in Nanyin playing, smoking and chatting, a trend sustained across the decades. In China as in Southeast Asia, changes in Nanyin paralleled the great transformations of their societies. In the context of Chinese nationalism for instance, master Chen Wuding’s (陈武定) song skits condemned the feudal system and its regressive society against the backdrop of a fallen Qing Dynasty. Beyond China, Nanyin witnessed and transformed alongside similarly momentous changes that Chinese immigrants experienced in places as diverse as Taiwan, Hong Kong, Indonesia and Singapore.5

The transformation of Nanyin alongside the unique sociocultural situations experienced by the Chinese diasporas across Southeast Asia evidently shows how society shapes the musical artform. For example, the promulgation of various discriminatory policies in 1966 in Indonesia saw the creation of Nanyin pieces that sought to record the difficulties faced by Chinese Indonesians during this period.6 In Taiwan, the genre is better known as nanguan (南管) and has over 200 documented societies since the early 18th century. It enjoyed strong support from Taiwan’s Nationalist cultural policy and ideology in its professed guardianship of Chinese culture during China’s Cultural Revolution.7 The above examples demonstrate the evolution of Nanyin in places where it has taken root. Thus, the history of Nanyin reflects the respective histories of the societies involved.

Nanyin’s changing audience: the case of Singapore

In Singapore, Nanyin began its life at the start of the 20th century as a connection with home amongst the Hokkien. As with other parts of the Chinese diaspora, Nanyin performing groups grew from a loosely gathered assemblage of Hokkien musicians into organised troupes that made the Hokkien distinct from other clan groups. Siong Leng Musical Association (湘靈音樂社會) was founded in 1941.8 It played at markedly Hokkien communal events such as the opening of the An Shun Hui An Gong Hui (安順惠安公會) in 1957.9 At this juncture, Nanyin music largely followed the tunes and legacies of the past – and rightfully so, for it served as a callback to the motherland for these Chinese migrants. Yet, identities change and naturally, this is reflected in music as well. Beginning in the mid-twentieth century, Nanyin’s changing audiences reflected the Hokkien’s assimilation into broader Chinese and Singaporean national identities.

After the Second World War, the Hokkien’s clan-based mode of organisation was increasingly being replaced by an emerging nationalism and changing regionalisms. The 1950s marked the height of Nanyin’s popularity in Nanyang (南洋). In 1954, Siong Leng Musical Association performed to raise money for the founding of Nanyang University, underlining its contribution to Chinese tertiary education in the region.10

Here, Nanyin takes a visible shift. While its ancient legacy is still very much preserved among the Chinese diasporas, new innovations are also introduced to reflect the sociocultural realities experienced by these diasporas.

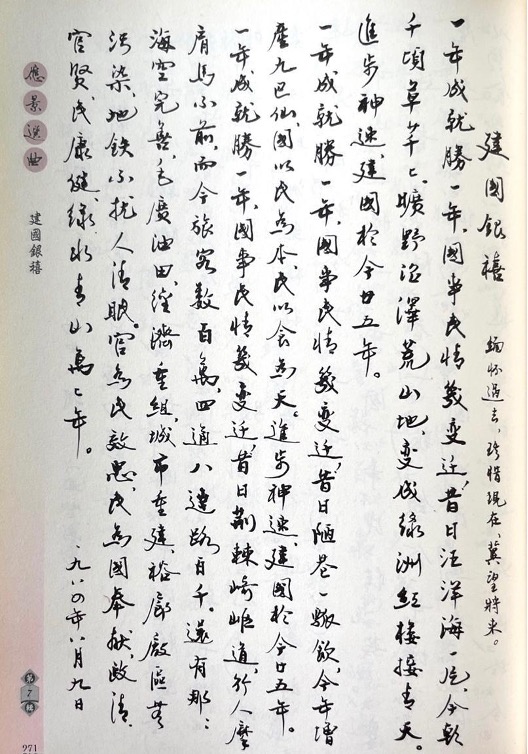

Figure 1 showcases a work by Teng Mah Seng (丁马成), a Nanyin practitioner based in Singapore. The piece is evidently different from typical Nanyin music scores, which concern themselves with the reflection of ancient courtly life or forlorn figures of love. Here, the focus is instead on documenting the globalising nature of Singapore’s landscape during the 1970s. The score discusses how Teng, who migrated during the 1920s, felt a sense of patriotism and awe at the speed of which Singapore developed during the twentieth century.11 The embers of nationalism have clearly set ablaze a change within the Singaporean-Chinese diaspora here. Chinese identity is no longer just a construct of their past in China, but also of their present in Singapore.

Nanyin today

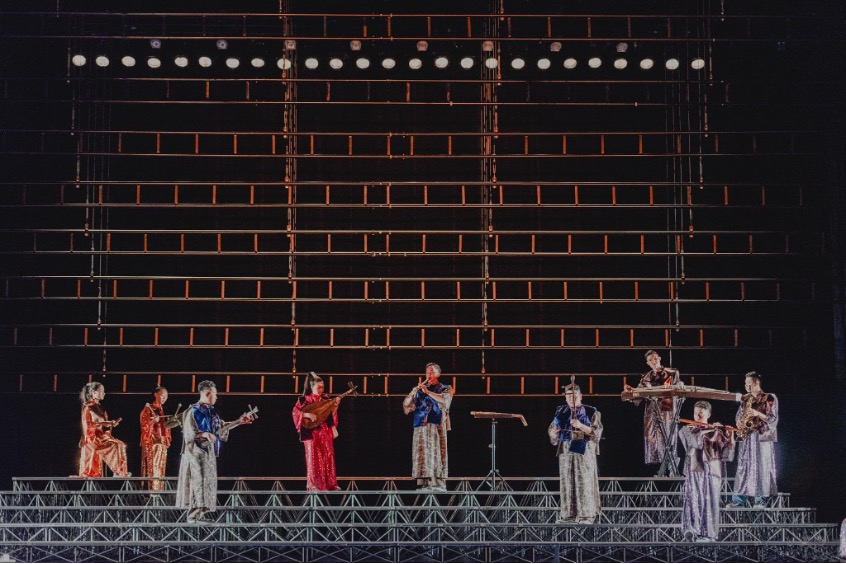

Today, Nanyin is recognised internationally as a cultural heritage by the Chinese diasporas around the Nanyang region. As Shzr Tan, a musicologist writes, this embroils the artform in a “politics of authenticity”, where many debate whether Nanyin played by diasporic artists can truly be considered true Nanyin.12 In the case of Singapore, organisations such as Siong Leng Musical Association, which fervently champions its role in preserving Nanyin, have been met with criticisms that its musical innovations and expressions are neotraditional.13 Not many have viewed innovations such as Teng’s to be reflective of Nanyin. For traditionalists, Nanyin is only viewed as legitimate when preserved in its timeless, unchanging and ancient form. Yet, such a criticism is not an isolated one. Taiwanese Nanyin organisations such as the Han-Tang Yuefu Music Ensemble (漢唐樂府) or the Xinxin Nanguan Ensemble (心心南管)have met similar criticisms in their attempts to integrate Nanyin with other genres of performance art such as modern dance. These are innovations driven by the need to appeal to younger audiences in a bid to preserve the art in the modern age. Given the reality of China’s cultural policies and the distinct histories of the Chinese diaspora, the attempt to pinpoint a cultural centre for Nanyin is deeply complex.

Conclusion

A legacy as well as memory dating back to the Tang Dynasty, Nanyin’s evolution bears witness to the rapid socio-cultural and political reconfigurations of the 20th century. In networks of the Chinese diaspora, Nanyin transitioned from being a cultural form unique to its Hokkien communities in the early 20th century into larger spheres of influence. By the 1960s, Nanyin was celebrated by the Chinese-educated rather than the Hokkien specifically – a testament to the expanding social sphere engulfed by the art. In Singapore, Nanyin took the further step of improved artistry and was performed internationally with a greater presence in English, rather than Chinese-educated spheres. Nanyin thus continues to be an interesting genre of music charting Singapore into a greater cosmopolitanism, in which the arts play an important role alongside economic growth.

Major References

1、Wang Yaohua and Liu Chunshu, Fujian Nan Yin Chu Tan (Fuzhou Shi: Fujian ren min chu ban she, 1989. 12.

2、Lim, Sau-Ping Cloris, “Nanyin Musical Culture in Southern Fujian, China: Adaptation and Continuity,” PHD Thesis, University of London, 2014. Read more for a detailed investigation of the musicology of Nanyin.

3、Lim, “Nanyin Musical Culture in Southern Fujian, China: Adaptation and Continuity.”

4、Lim, “Nanyin Musical Culture in Southern Fujian, China: Adaptation and Continuity,” 158.

5、Wang and Liu, Fujian Nan Yin, 12.

6、陈敏红, “‘物’化的南音——印尼东方音乐基金会‘南音人’口述史研究,” Yin yue yan jiu, no. 1 (2018): 92.

7、Lim, “Nanyin Musical Culture in Southern Fujian, China: Adaptation and Continuity.”

8、Poh Chin Chor, “Teng Mah Seng,” NLB Infopedia eResources, January 14, 2014, https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/infopedia/articles/SIP_2014-01-24_114302.html.

9、 “An Xun Hui Tong An Kongsi Opens Tomorrow [安順惠安公會新會所明日開幕],” Nanyang Siangpau[南洋商报], November 15, 1957, https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/newspapers/Digitised/Article/nysp19571115-1.2.41.2?ST=1&AT=search&k=%22%E5%8D%97%E7%AE%A1%E6%A8%82%22&QT=%22%E5%8D%97%E7%AE%A1%E6%A8%82%22&oref=article.

10、 “Siong Leng Musical Association Aids in Nanyang University Funda-Raiser[湘靈音樂社籌備 爲南大舉行義演],” Xinzhou Ribao[星洲日報], August 9, 1954, https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/newspapers/Digitised/Article/scjp19540809-1.2.47?ST=1&AT=search&k="湘靈" "南音"&QT="湘靈","南音"&oref=article; Kok-Chiang Tan,My Nantah Story: The Rise and Demise of the People’s University (Singapore: Ethos Books, 2017).

11、 卓聖翔曲 ; 丁馬成詞 ; 林素梅主唱 et al., 應景選曲, Chu ban (Gao xiong shi: 鄉音, 2002), 271.

12、Tan Shzhr Ee, “Unequal Cosmopolitianisms, Staging Singaporean Nanyin in and beyond Asia,” in Asian City Crossings: Pathways of Performance through Hong Kong and Singapore, ed. Rosella Ferrari and Ashley Thorpe (Abingdon, Oxon; New York: Routledge, 2021), 104.

13、Tan, “Unequal”, 105.

Bibliography

1、Chor, Poh Chin. “Teng Mah Seng.” NLB Infopedia eResources, January 14, 2014. https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/infopedia/articles/SIP_2014-01-24_114302.html.

2、Fumitaka, Yamauchi. “Contemplating East Asian Music History in Regional and Global Contexts.” In Decentering Musical Modernity: Perspectives on East Asian and European Music History, edited by Tobias Janz and Chien-Chang Yang. Music and Sound Culture = Musik Und Klangkultur 33. Bielefeld: Transcript, 2019.

3、Leung, Paul Kin Hang. “‘The Southern Sound’ (Nanyin): Tourism for the Preservation and Development of Traditional Arts.” Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research 9, no. 4 (December 2004): 373–82. https://doi.org/10.1080/1094166042000311255

4、Lim, Sau-Ping Cloris, “Nanyin Musical Culture in Southern Fujian, China: Adaptation and Continuity,” PHD Thesis, University of London, 2014. Read more for a detailed investigation of the musicology of Nanyin.

5、Nanyang Siangpau[南洋商报]. “An Xun Hui Tong An Kongsi Opens Tomorrow [安順惠安公會新會所明日開幕].” November 15, 1957. https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/newspapers/Digitised/Article/nysp19571115-1.2.41.2?ST=1&AT=search&k=%22%E5%8D%97%E7%AE%A1%E6%A8%82%22&QT=%22%E5%8D%97%E7%AE%A1%E6%A8%82%22&oref=article.

6、Shin Min Daily News[新明日报]. “At Vesak Day, Siong Leng Musical Association Plays Nanyin [觀音聖誕 湘靈音樂社 奏南音錦曲].” April 7, 1977. https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/newspapers/Digitised/Article/shinmin19770407-1.2.68?ST=1&AT=search&k=%22%E6%B9%98%E9%9D%88%22%20%22%E5%8D%97%E9%9F%B3%22&QT=%22%E6%B9%98%E9%9D%88%22,%22%E5%8D%97%E9%9F%B3%22&oref=article.

7、TAN Ah Hiang. Interview by Yuhang Chen, January 17, 2019. Accession number E00921. Nam Hwa Opera Collection.

8、Tan, Kok-Chiang. My Nantah Story: The Rise and Demise of the People’s University. Singapore: Ethos Books, 2017.

9、 Tan, Shzr Ee. 2021. “Unequal Cosmopolitianisms. Staging Singaporean Nanyin in and beyond Asia.” In Asian City Crossings: Pathways of Performance through Hong Kong and Singapore, edited by Rossella Ferrari and Ashley Thorpe. Abingdon, Oxon ; New York: Routledge.

10、 Xinzhou ribao[星洲日報]. “Siong Leng Musical Association Aids in Nanyang University Funda-Raiser[湘靈音樂社籌備 爲南大舉行義演].” August 9, 1954. https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/newspapers/Digitised/Article/scjp19540809-1.2.47?ST=1&AT=search&k="湘靈" "南音"&QT="湘靈","南音"&oref=article.

11、Yaohua, and Chunshu. Liu. Fujian Nan yin chu tan / Wang Yaohua, Liu Chunshu zhu. Fuzhou di 1 ban. Fuzhou Shi: Fujian ren min chu ban she, 1989.

12、联合早报. “发扬南音丰富文化.” 联合早报, June 29, 1987.

13、陈敏红. “‘物’化的南音——印尼东方音乐基金会‘南音人’口述史研究.” Yin yue yan jiu, no. 1 (2018): 85–93.

14、卓聖翔曲 ; 丁馬成詞 ; 林素梅主唱, 卓聖翔., 丁馬成., and 林素梅. 應景選曲. Chu ban. Gao xiong shi: 鄉音, 2002.

All articles/videos are prohibited from reproducing without the permission of the copyright holder.

Welcome to leave a message:

Please Sign In/Sign Up as a member and leave a message南音文化,這使我想起美國有藍調音樂!是黑奴感懷身世,而應運而生的一種音樂,與中華南音有異曲同工之效!

多謝兩位學者分享!🙏

#1

Chi Seng Pun

02-03-2023 10:55:13

南音文化,這使我想起美國有藍調音樂!是黑奴感懷身世,而應運而生的一種音樂,與中華南音有異曲同工之效!

多謝兩位學者分享!🙏

#2

Chi Seng Pun

02-03-2023 10:54:58