The Circulation of Chinese Calligraphy in East Asia

As an art of writing, calligraphy originates in China, with a history as long as Chinese characters. Since the birth of oracle-bone inscriptions, Chinese characters have developed five different calligraphic styles, namely, seal script (篆書), official script (隸書), cursive script (草書), regular script (楷書), and running script (行書). Calligraphers write with the ink brush and decorate the works with seals for diverse aesthetic forms. In the process, they have developed abundant and comprehensive calligraphy theories based on their personal experiences, thus forming a profound Chinese calligraphy tradition and exerting a great impact on the study of calligraphy for future generations among Asian societies. Chinese calligraphy has had a wide popularity in the regions influenced by the Chinese culture, including Korea, Japan, the Ryukyu Islands, Vietnam, Singapore, etc. Calligraphy is known as “Shu Fa” (書法, meaning “the way of writing”) in China, Vietnam, Singapore, and Malaysia, “Seoye” (書藝, “the art of writing”) in Korea and “Shodō” (書道, “the Way of writing”) in Japan.

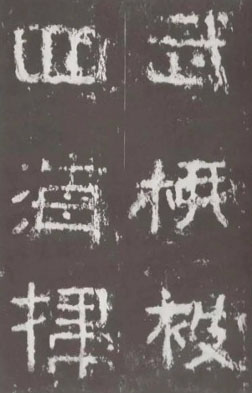

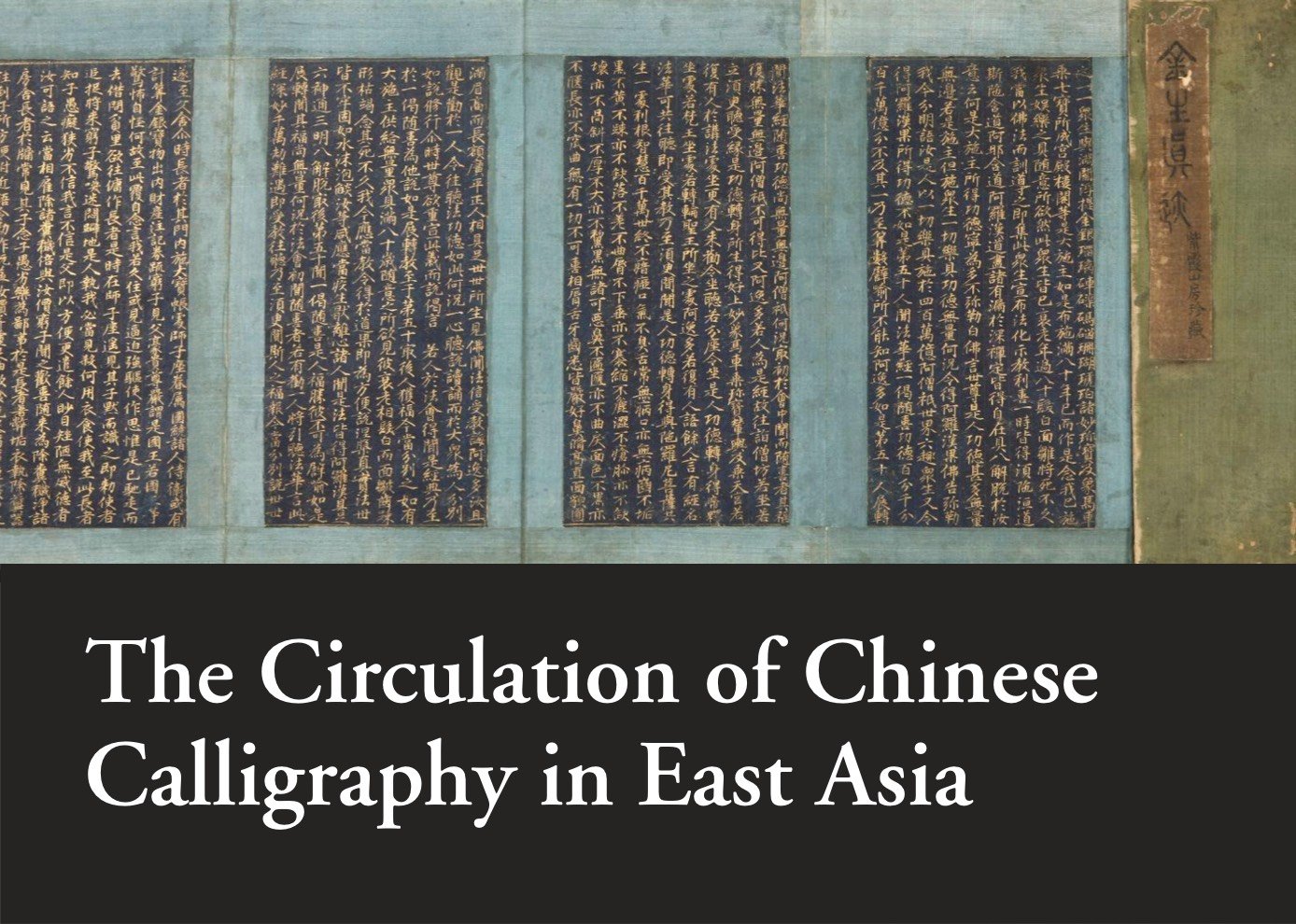

Unearthed during the Guangxu period of the Qing Dynasty (清光緒年間,around 1880). Carved in the tenth year of the Yixi reign of the Eastern Jin Dynasty (東晉義熙十年,414). Official script.

612x185cm, 44 lines, 41 characters in each line. Located in Ji’an, Jilin Province in northeast China.

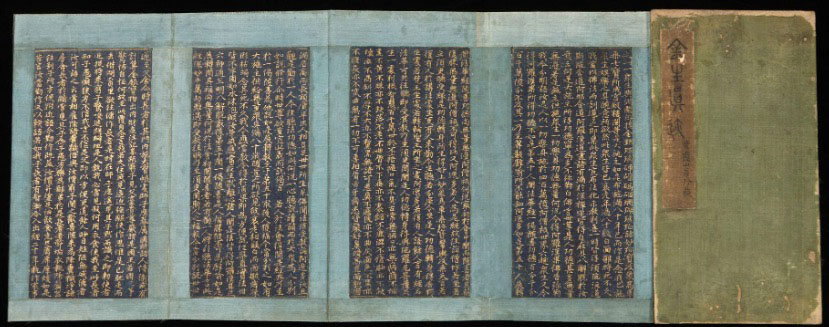

Chinese characters were first adopted by Korea around the 2nd or 3rd century, and “Seoye” began to develop at the same period. After Korean alphabets were created in 1446, Chinese characters were still served as official characters until the end of the 19th century, indicating a long and rich history of “Seoye” in Korea.

The “Gwanggaeto Stele” in Ji’an (Figure 1), built during the reign of Gwanggaeto the Great (好太王,391-412), is the oldest surviving Goguryeo (高句丽, also spelled as Koguryo) stone tablet. About 1,800 characters are inscribed in standard official script, with vivid strokes and clear structure. Subsequently, the reverence for Chinese culture of the Tang Dynasty gave rise to many great calligraphers in Korea, such as Kim Saeng (金生,711-791) (Figure 2) and Choi Chi-won (崔志遠,857-?). They basically followed the Chinese calligraphers in the early Tang Dynasty like Ouyang Xun (歐陽詢,557-641) and Yu Shinan (虞世南,558-638).

Later, the Korean culture underwent changes due to the Japanese colonial rule (1910-1945). During this time, Korean calligraphy works were clearly influenced by the Japanese style, bearing the features of loose strokes, natural structure, and flexible organization. After the 1960s, there was a new trend of writing with Korean alphabets, which led to the decline of traditional calligraphy. During this period, an artistic giant named Sohn Jaehyuung (孫在馨, 1903-1981) emerged, who named Korean calligraphy “Seoye” to highlight its national characteristics.

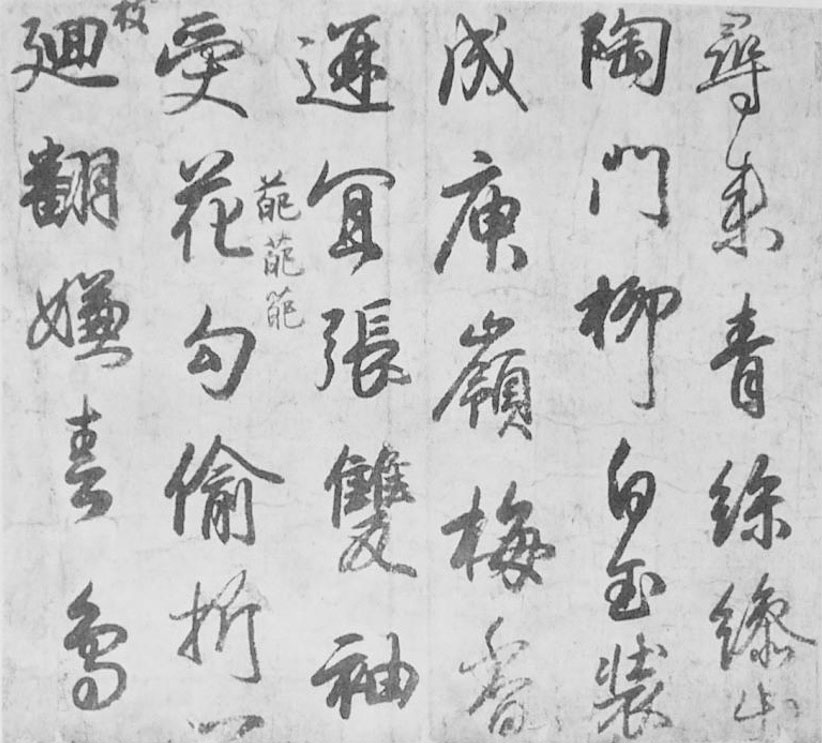

Japan first learnt Chinese characters from Baekje in Korea in the 5th century. Initially, they did not master the art of calligraphy, and it was not until the Nara period (奈良時代,710-794) and early Heian period (平安時代,794-1185) that several calligraphers emerged, such as Saga Tenno (嵯峨天皇,786-842), Kukai (空海,774-835), and Tachibanano Hayanari (橘逸势,782-842). Ancient Japan was so enamored of Chinese Han and Tang culture that most Japanese calligraphers imitated the handwriting of Chinese calligraphers, which gave rise to the artistic style known as “Japanese aesthetics”. The “Draft on the Screen” (屏風土代Figure 3) is a masterpiece written by Ono Michikaze (小野道風,894-967), one of the “Three Great Calligraphers” of the Heian period, in response to the will of Daigo Tenno (醍醐天皇,885-930). The work records a seven-character poem written by a Japanese poet, Oe no Asatsuna (大江朝綱,886-958).

The ancient cave faces a clear river in spring,

(古洞春來對碧灣,)

tea smoke and clouds flow leisurely at dusk.

(茶煙日暮與雲間。)

Mountains stand with their back to the setting sun,

(山成向背斜陽里,)

and the current of the river is fast.

(水似回流迅瀨間。)

The snow melts, and the green grass grows,

(草色雪晴初布護,)

the day warms up with the singing of the birds.

(鳥聲露暖漸綿巒。)

There is a traveler alone on the bridge of the river,

(誰知圮上獨遊客,)

like he is going to return the old man’s shoes.

(疑是留侯授履還。)

The poem follows the style of Tang Dynasty, paying attention to language norms and phonological formats such as sentence lines, sentence structures, tonal patterns, antithesis, rhyme, and allusion. The handwriting is mainly in cursive style, with rich character shapes, concise structure and smooth strokes, making the work both grand and majestic. Up to now, Chinese calligraphy has taken root in Japan and become a distinctive form of art with its own national characteristics. In 2020, the Japanese government included “Shodō” as one of Japan’s national art projects for cultural exchanges with foreign countries.

Reference

Book

1. 陳振濂:《日本書法史》(沈陽:遼寧教育出版社,1996年)。

Dissertation

1. 辛勛:《論朝鮮後半期書法藝術的發展兼論韓中書法交流》(復旦大學博士學位論文,2009年)。

All articles/videos are prohibited from reproducing without the permission of the copyright holder.

Welcome to leave a message:

Please Sign In/Sign Up as a member and leave a message