The Past and Present of Suzhou Pingtan (2): Suzhou Pingtan, Catering for Both Refined and General Tastes

Speaking of quyi (曲藝), we may think that it is a vulgar culture and belongs to the grassroots. Pingtan, as one of the forms of quyi, however, is regarded as the orchid of it. The difference between pingtan and other forms of quyi is that it caters for both refined and general tastes. Suzhou has been a place endowed with prosperous economy and culture. In the Qing Dynasty (1616-1911), there were 26 zhuangyuan (the scholars who come out first in the highest imperial examination狀元) in Suzhou, accounting for 22.8% of the country’s total. There is no wonder that Suzhou people are proud to say that Suzhou has two specialties, one is top scholars (狀元), and the other is top stars (優伶), specifically, pingtan and kunqu (崑曲) artists.

With prosperous material and cultural life, the people in Suzhou have a great demand for leisure and entertainment and display an extremely high level of artistic appreciation. That’s why both kunqu, the orchid of Chinese opera, and pingtan, the orchid of Chinese quyi originated in Suzhou.

Suzhou pingtan has gradually evolved from popular culture to being appreciated by both refined and popular audiences. On the one hand, storytellers must read many books to tell good stories. They face on-the-spot criticism and evaluation from the audience. Once they make a mistake or have a weak logic, they will be discussed or evaluated afterwards by audiences in the teahouse. In addition, storytellers face fierce competition among peers, so they have to constantly strive for refinement and perfection. On the other hand, literati, gentry and officials are also deeply attracted by pingtan. When they gather together, they may invite storytellers to perform at family parties or visit story houses for their performance. In this way, they make friends with pingtan artists, help them improve their cultural level and revise scripts. They even become amateur players themselves, constantly pushing pingtan towards refinement.

This inscription Zhu jia gao tan (literally cupping the cheek and talking with eloquence拄颊高谈) is written by the Minister of Education during the Republic of China (1912-1949) at the request of Guangyu Society. The phrase is taken from a poem written by Wu Meicun (吳梅村, 1609-1672) about Liu Jingting (柳敬亭, 1587-1670), the forefather of storytellers, which means that the pingtan artists spend their whole life telling stories, thinking and talking at the same time. They are not just ordinary artists, but masters.

There are many anecdotes about the interaction between literati, gentry, officials, and storytellers.

Wang Yincai (王引才), the educator, returned to his hometown Nanxiang (南翔), Shanghai after he resigned the position of the head of Wuxian County (吳縣), Suzhou. He was a regular visitor in the story houses and showed particular interest in the performance by Chen Ruilin (陳瑞麟,1905-1986) and his brother. At nine o’clock every morning, Mr. Wang gathered some local gentlemen and celebrities, about forty or fifty people, to enjoy the tanci (彈詞) performance by the Chen brothers on the dry boat in the classical Guyi Garden (古漪園). Surrounded in such a beautiful and peaceful environment and indulged in such a delicate and pleasant performance, all the guests present expressed their utmost appreciation and satisfaction. Everyone was in such high spirits that they sometimes offered their suggestions, from which the Chen brothers benefited a lot. Wang Yincai even wrote a poem about the art, which warned the performers to be cautious in the words and contents of the stories (“莫笑弹词戏一场,说来说去是家常;神权帝制今休护,科学还宜细考量”). In the form of storytelling, they should transmit correct values to the listeners, not the old-fashioned ideas of gods and monsters.

Xu Xueyue (徐雪月, 1917-2000), one of the eighteen artists who founded the Shanghai Pingtan Troupe (上海評彈團), is widely regarded as a talent in storytelling. Her admirers, including many famous scholars and celebrities, formed a “Snow Society” (Xue she雪社), whose members were all experienced in listening to stories. They were willing to guide and teach her in order to improve her writing skill whenever she was free. In particular, a group of fans in Shanghai helped Xueyue to edit the script Three Smiles (Sanxiao三笑), removing the unnecessary parts and adding some valuable notes and poems to it for the better effect. They also guided her on how to play the part in the story to make it full of Kunqu flavor for the perfection. This is similar to the situation that some scholars helped Ma Rufei (馬如飛) to revise his Pearl Pagoda (《珍珠塔》) several times.

There is another story about a female tanci performer named Wang Meiyun (王梅韻, 1922-2022). The literati Wu Xingweng (吳興翁) invited her for the long-term performance at home. But actually Wu also enthusiastically guided her to improve her storytelling skills and taught her how to read, write and make poems. He even taught her how to draw plum blossom just because there is a character of plum (mei 梅) in her name. Wu and other literati had decades of experience in listening to storytelling. They could remember clearly the performances of those top artists in the previous years, so they shared with Wang Meiyun about these situations.

The banking community in Shanghai was also fond of Suzhou pingtan and established a club of amateur performers called Yinlian she (literally Bank Union Club银联社). These club members were wealthy and well-educated, so they organized the activities frequently. Once they held a temporary storytelling performance in Wuqufang (吳趨坊), Suzhou and invited top artists including Pan Boying (潘伯英, 1903-1968), Zhang Jianting (張鑒庭, 1909-1984) and his brother, Tang Gengliang (唐耿良, 1921-2009), and Jiang Yuequan (蔣月泉, 1917-2001) to perform together. The audiences gathered in a moment and crowded in the open-air square. Among the guests, some famous amateur performers from the Bank Union Club and Huang Jinzhi, the editor-in-chief of the Storytelling Weekly (《书坛周讯》), performed on stage and were also popular.

The gentry and local officials also visited the story houses. There is a gentry called Zuo Ji in Changshu, Jiangsu Province, who once wrote a series of “Miscellaneous Poems about the Story Houses”, truly depicting the grand occasion at that time. One of the poems is about Zhu Ji’an (a tanci artist of the Qing Dynasty with birth and death years unknown). Zhu Ji’an, a native of the county, created the tanci story of Romance of the West Chamber (Xixiang ji《西厢记》). He had the special skills in speaking, joking, music playing and singing and had a high reputation in the Jiangnan area. When he performed at the Garden Yuhuchun (literally Jade Pot Spring玉壶春), the gentry of the county, who were not interested in storytelling, admired him and came in sedan chairs. There were as many as thirteen sedan chairs waiting at the gate.

People often comment that without pingtan, Jiangnan would no longer be the Jiangnan in our minds, which describes the weight of pingtan in Jiangnan culture. The communication of pingtan artists representing popular culture and literati and gentry representing elite culture endows pingtan with the characteristic of being both popular and refined, which makes Jiangnan culture more rational.

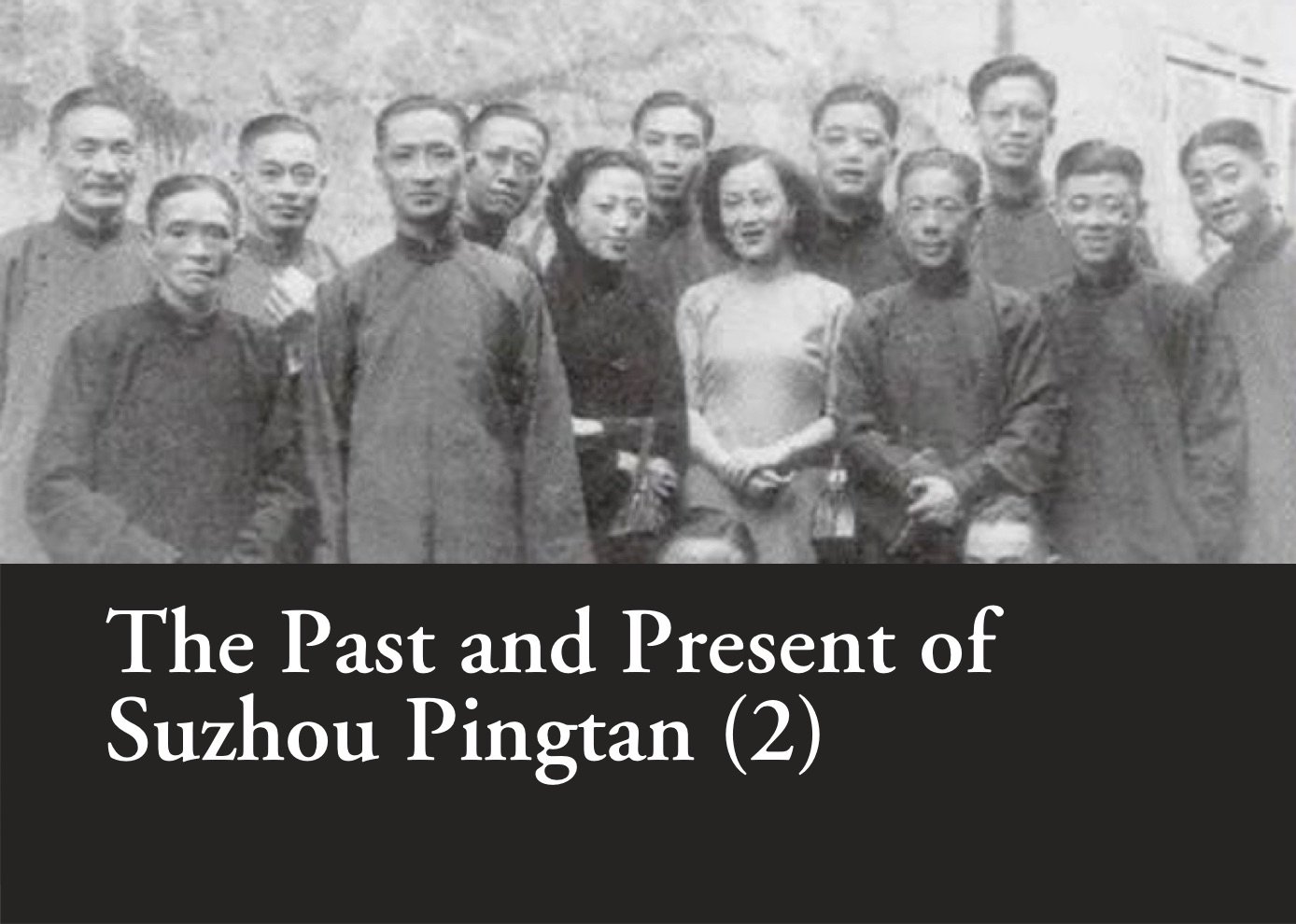

Left image: A group photo of storytellers in the early years of the founding of the People's Republic of China

Middle image: Signature of the Pingtan artist at the gathering

The right image: A poem written by the talented storyteller Huang Yian (黃異庵)

All articles/videos are prohibited from reproducing without the permission of the copyright holder.

Welcome to leave a message:

Please Sign In/Sign Up as a member and leave a message