The Spread of Chinese Calligraphy to Southeast Asia

The art of calligraphy in Singapore and Malaysia has developed with the immigration of Chinese people to this region. From the early 20th century to the mid-1960s, Chinese were the majority ethnic group in Singapore and Malaysia. The fact that about 70% of Singapore’s population was Chinese could be a good proof. Undoubtedly, the traditional Chinese culture deeply influenced the ideology of local residents, and Chinese language and culture education naturally received great attention. In the Malay Peninsula, the earliest Chinese language and culture education began in 1819 when the first academy “Ng Fook Thong Temple” (五福書院) was set up in Penang. It was built by Chinese immigrants from five counties in Guangdong Province, including Nanhai (南海), Panyu (番禺), Shunde (順德), Xiangshan (香山), and Dongguan (東莞). The academy followed the tradition of Chinese private schools and employed teachers from mainland China to teach children courses like Chinese language, history, geography etc. What’s more, students were taught to learn Chinese characters by tracing the given characters or imitating them on another paper according to the tradition.

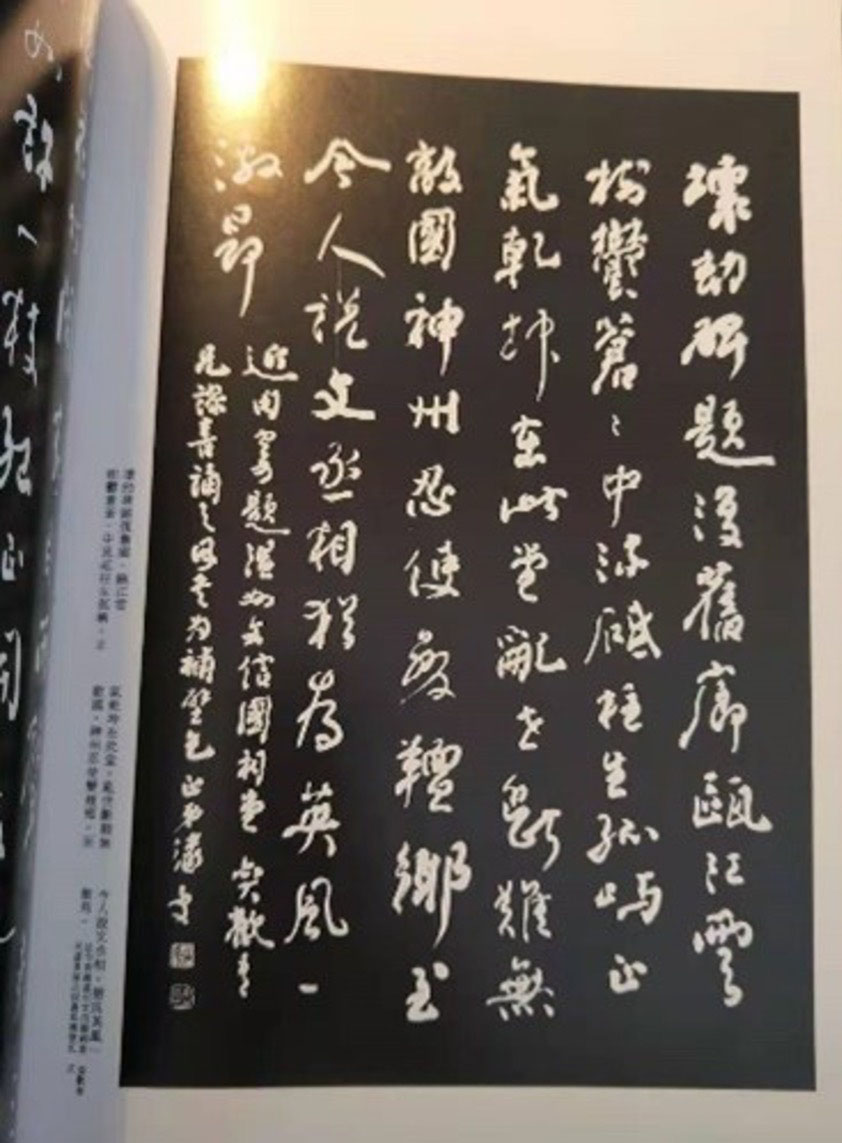

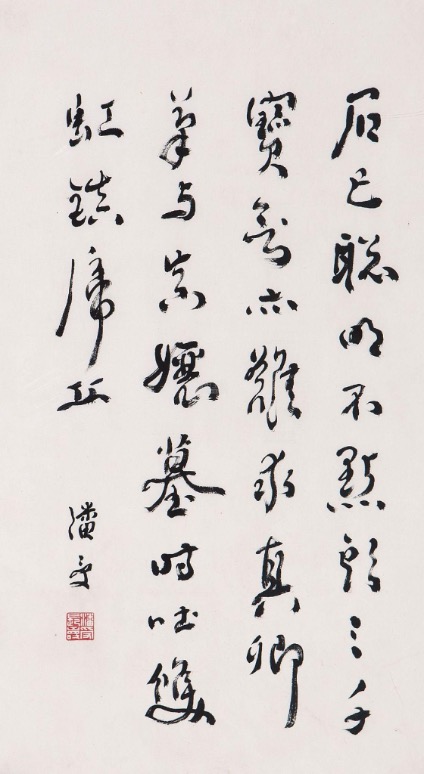

In the 1920s and 1930s, the Southeast Asian art circles saw the emergence of the independent movement with the “Southeast Asian Style” in Singapore and Malaysia. After the WWII, the viewpoint emphasizing local style began to receive widespread attention and led to the trend of developing local literature and art. In 1948, after the debate between “Malaysian Chinese Art” and “Overseas Chinese Art”, the standpoint on “independence of Malaysian Chinese literature and art” gradually became mainstream. Pan Shou (潘受,1911-1999) was one of the representatives at that time, who mainly reflected the “localism” through his poetries. He has a high level of expertise in poetry and leaves behind a large number of works, such as Overseas Chinese Poetries (《海外盧詩》) and Pan Shou’s Calligraphy Works (《潘受墨跡》). As a calligrapher and poet, Pan writes his own poems in calligraphy, expressing his understanding and emotions towards the surrounding environment. The expression is direct, without the secondary processing by others, so is a perfect reproduction of his original creative intention.

However, the development of Chinese calligraphy encountered difficulties in the mid-20th century. In 1957, Singapore and Malaysia got rid of colonial domination, and the government immediately issued the 1961 Education Act to restrict the development of local Chinese language and culture education. As a result, the popularity of Chinese calligraphy was severely affected. Pan Shou, hailed as one of the most treasured calligraphers in Singapore, witnessed the ups and downs of calligraphy development in Singapore and Malaysia during this period. Pan was born in a scholarly family in Nan’an, Fujian Province. After he migrated south to make a living in 1930, he first worked as an editor for “Ye Lin” (《椰林》), the supplement of “Lat Pau” (《叻报》) (the earliest Chinese newspaper in Singapore, 1881-1932). Later, he became the principal of Chongzheng School in Singapore, dedicating his whole life to promoting Chinese language and culture education and calligraphy development in Singapore and Malaysia. In terms of his calligraphy, Pan mainly follows the styles of Yan Zhenqing (顏真卿, 709-784) and Yu Shinan (虞世南, 588-638). He inherits the characteristics of Yan by keeping the brush tip along the center of each stroke in order to make it round and heavy. Also, he particularly follows the pattern of “writing in a line vertically while not in a row horizontally” to make the writing look both neat and free. These techniques help him develop his grand and graceful style and exert a great influence on calligraphy learners in Singapore and Malaysia. (Figure 2) At the end of the 20th century, with the normalization of Sino-US relations, the easing of the Cold War situation in the Asia Pacific region, and the successful takeoff of the modern Chinese economy, the value of Chinese language was once again elevated. The Singapore and Malaysia governments initiated measures to promote Chinese language, leading Chinese calligraphy to a period of vigorous development once again.

With the passage of time, the practical function of calligraphy has gradually declined, but the artistic, social, and cultural values that it carries are advancing day by day. Calligraphers express their personal spirit and inner emotions in calligraphy, thereby displaying their understanding of the world and the significance of living. Calligraphy originates in China, however, its influence has gone far beyond that. Due to the influence of unique geographical environment and historical culture, calligraphy in different countries has adopted different ethnic characteristics, which leads to the flourishing of Chinese calligraphy in Asian countries. In the context of increasingly interconnected relations among countries globally, we should break out of our inherent knowledge framework and explore the diversity and possibilities of calligraphy art from a broader cultural perspective, so that we could enrich our understanding of the cultural connotations of Chinese calligraphy.

Reference

Book

1. 謝光輝、陳玉珮:《新加坡、馬來西亞華文書法百年史》,廣州:濟南大學出版社,2013年。

Journal Article

1. 馬峰:<華文詩歌中的百年嬗變—評朱文斌《東南亞華文詩歌及其中國性研究》>,《文藝爭鳴》,2018年第5期,頁155—160。

Dissertation

1. 蔡息園:《潘受的書法藝術》(廣州中山大學碩士學位論文,2019年)。

All articles/videos are prohibited from reproducing without the permission of the copyright holder.

Welcome to leave a message:

Please Sign In/Sign Up as a member and leave a message