The Oneness of Tea and Chan

One day in the afternoon, my friend invited me to a tea gathering. We leisurely walked to the elegant and quiet tea room and sat down on a light green sofa basked in the warmth of the sun. Sipping the fragrant tea, I felt relaxed and noticed the small plaque hanging behind the tea master saying “Oneness of Tea and Chan.” (茶禪一味) I was curious about it and asked my friend for his understanding. “It’s like drinking water. Each person has their own understandings.” With some research, I got my understandings and would like to share it with you for more valuable opinions.

In order to understand the concept of “oneness of tea and Chan”, let’s first briefly examine the impact of Confucianism, Buddhism, and Taoism on Chinese tea culture, from which it got its essence. Originating from the romanticism of Taoism, being centered on Confucian’s active participation in the real world and developed in Buddhist tranquility and detachment, tea tasting is finally evolved into a life enjoyment of purity, integrity and virtue.

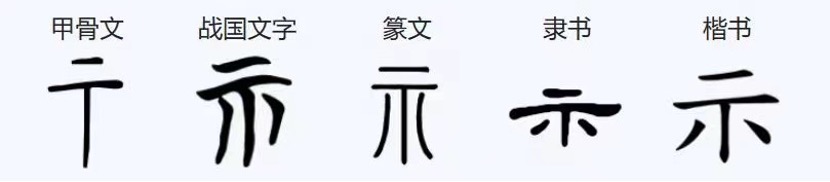

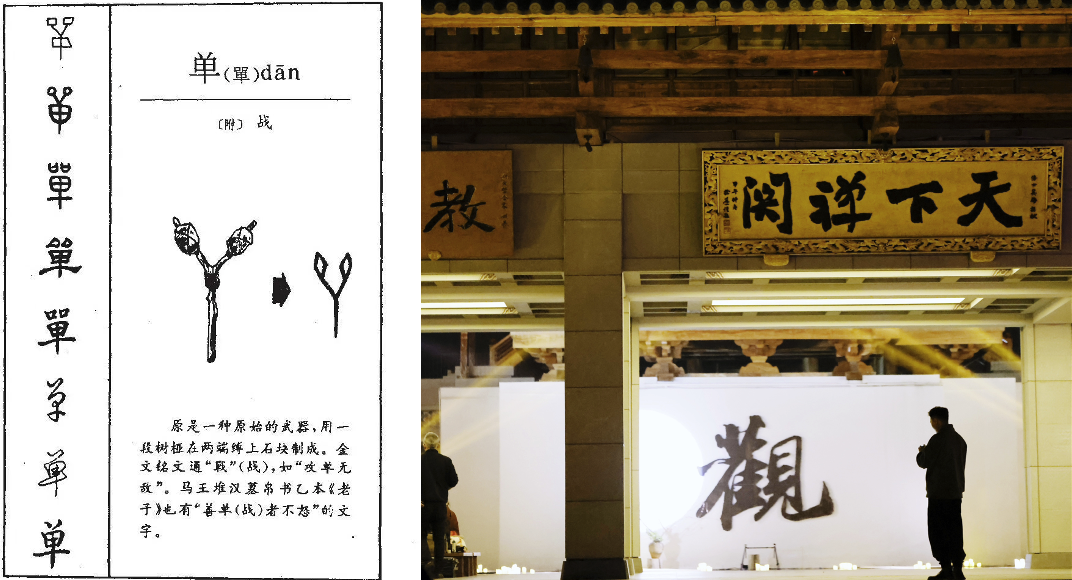

What is “Chan”? Lou Yulie (樓宇烈), the contemporary scholar of Chinese culture, once said that “It’s both difficult and easy to understand it.” By analyzing the character Chan (禅), we can see that the origin of the radical side is “示”, representing the sacrificial table in the ancient time, related to the worship of gods. The right side of the character is a pictogram of “单”, which is derived from the shape of ancient hunting tools as well as important weapons and also the slingshot we play as kids. Therefore, “单” is related to hunting and war, meaning “to be alone” and “free from distracting thoughts”. Putting the two parts together, Chan (禅) has the meaning of grand sacrificial ceremony, worshiping heaven and praying for blessing and peace. Kumārajīva (鸠摩罗什, 343-413) translated “Chan” into “thinking practice” and Xuan Zang (玄奘, 602-664) translated it into “meditation”, a way of sitting quietly and meditating on one’s own mind.

The text of Picture 2: Originally a primitive weapon, the pictogram of “单” symbolizes the attaching of stones to a tree branch at both ends, which is the same as “戰” (fighting or war) in the bronze inscriptions, as shown in the expression “攻單無敵” (Gong dan wu di, invincible in attack) . The second edition of the silk book Laozi (also known as Tao Te Ching) unearthed from the Mawangdui Han Tomb also has the words “those who are good at fighting will not burst into anger,” in which “單” (being alone) and “戰” (fighting or war) are interchangeable.

The text of Picture 2: Originally a primitive weapon, the pictogram of “单” symbolizes the attaching of stones to a tree branch at both ends, which is the same as “戰” (fighting or war) in the bronze inscriptions, as shown in the expression “攻單無敵” (Gong dan wu di, invincible in attack) . The second edition of the silk book Laozi (also known as Tao Te Ching) unearthed from the Mawangdui Han Tomb also has the words “those who are good at fighting will not burst into anger,” in which “單” (being alone) and “戰” (fighting or war) are interchangeable.

The origin of Chan Buddhism is attributed to Śākyamuni (释迦摩尼, who lived in the same era as Confucius). At the Lingshan Dharma Assembly, Śākyamuni showed off his golden pomelo flower to the public, at which the disciples were all puzzled. Only Mahākāśyapa (迦叶尊者) broke his face and smiled to receive the true transmission. This is the origin of Chan and also the allusion of “smiling at the flower”. During the Southern Dynasties (420-589), Bodhidharma (?-536) traveled eastward and introduced Chan Buddhism to China. Later, Huineng (638-713) founded the Southern Chan and further promoted the spread of Chan in China.

The encounter of tea and Chan can be traced back to the Han Dynasty (206BC-220AD). In Mengding, Sichuan Province, Wu Lizhen pioneered the concept of “unity of Buddhism and tea (茶佛一家)”. He is known as the first to cultivate tea in temples in Chinese history and is referred to as the Ganlu Chan Master. Buddhism gradually became localized during the Tang Dynasty (618-907) with the emergence of many rules and regulations, such as abstaining from alcohol and no eating after the noontime. On the one hand, tea can refresh the mind and relieve drowsiness, making it a necessity for monks during the sitting meditation. On the other hand, the popularity of Chan needs a common medium with the public, therefore, tea has become the preferred choice for monks. In his Hundreds of Buddhist Regulations, Chan Master Huaihai (720-814) incorporated tea drinking into the temple tea ceremony and tea planting and tea making became compulsory agricultural activities of monks. In the late Tang Dynasty, with the popularity of tea drinking, Chan monks adopted tea as a medium to communicate with literati and scholars during their study tours. Thus, the idea of “oneness of tea and Chan” was formulated. In the Song Dynasty (960-1279), Keqin (1063-1135) incorporated the infinite mysteries of tea with the concept of Chan and formally put it into words as “oneness of tea and Chan.” An eminent monk once said, “Carrying water and firewood is nothing but the Tao; living, walking, sitting, and sleeping is nothing but Chan.” Nowadays, Chan has transcended the realm of religion and become a form of culture and life. Japanese monk Eisai (1141-1215) brought back the tea and Chan Buddhism to Japan and developed the practice into tea ceremony. When coming to Britain, it turned into a romantic afternoon tea. At 4 p.m., Duchess Anna prepared black tea and pastries and invited her friends to taste Qimen Lanxiang, the Queen of Black Tea from the oriental country.

In Chan Buddhism, there is an anecdote of “going and drinking tea” related to Ancient Buddha Zhaozhou (趙州古佛,778-897), who is also known as the “Ancient Buddha of Zhaozhou”. He often told scholars to go and drink tea no matter where they were from. It is said that two monks came to the Guanyin Temple where he resided and asked about Chan. The Master asked one of the monks, “Have you ever been here before?” The monk answered no. The Master said, “Go and drink tea.” Then he told the other monk the same when the monk said he had been here before. The person leading the way was puzzled and asked, “Do both of them go and drink tea?” The Master asked the temple supervisor to go and drink tea as well. In this way, those who have not come before will have the experience of drinking tea, those who have come and drunk tea will start to think, and temple supervisors will have reflections. Therefore, the behavior and mentality of “going and drinking tea” are actually the representation of the Chan philosophy, which will suit every person in different ways. The relationship between tea and Chan became even closer afterwards. Chan is simple, natural, and harmonious, and the same goes for the fun of drinking tea. There is Chan in tea and tea in Chan. Life is Chan and Chan is the realization of life.

The poet Su Shi (蘇軾,1037-1101) once wrote that: “Tea and bamboo shoots are the flavor of Chan, pine and fir trees are the sound of Buddhism.” Chinese tea culture, with the Confucian spirit as the core, absorbs Chan culture and becomes the external carrier of Chan culture. Tea culture and Chan culture are in harmony with each other, one external, one internal, one tangible, one intangible, one yin and one yang. The concept of “oneness of tea and Chan” is not only a way of life, but also a philosophy of life.

In early summer, by the mountain stream spotted with orchids, light a stick of incense, lay out a tea mat adorned with azalea patterns, and brew a cup of Mengding Sweet Dew. As the fragrant smoke curls and drifts freely, the Dongshan bell tolls, it’s time to enjoy the tea.

Reference :

Book

1. 李潤生:《禪宗公案》(臺北:方廣文化事業有限公司,2016年)。

2. 王玲:《中國茶文化》(北京:九州出版社,2009年)。

All articles/videos are prohibited from reproducing without the permission of the copyright holder.

Welcome to leave a message:

Please Sign In/Sign Up as a member and leave a message