Little Tradition in the Chinese Four Classics

This article is an excerpt from Prof. SUN, Tien-Lun 's book,

Edited by Shen Shilin, Loke Kok Kuen Chinese Cultural Legacy Research Trust Researcher.

INTRODUCTION:

The Great Tradition and the Little Tradition

According to Redfield (1956), there is a great tradition and a little tradition in every civilization. The great tradition is that of philosophers, theologians, and learned people, and is one that has been consciously and conscientiously cultivated and passed on through generations. Until educational opportunities became accessible to the majority of people, the great tradition had been available to only a few educated men. The little tradition, on the other hand, belongs to the ordinary people. It evolves with the lives of these people and is self-propelling for the simple reason that tradition is vital in the creation of a sense of belonging. The great tradition is recorded in the classical texts, whereas the little tradition is available to the messes through oral transmission by storytellers and theatre troupes, with some of the stories becoming popular novels. The great and little traditions are interdependent and mutually influential. It is not possible to indicate where one begins or where the other ends, rather they tend to penetrate each other, and in the process, cause changes in each other.

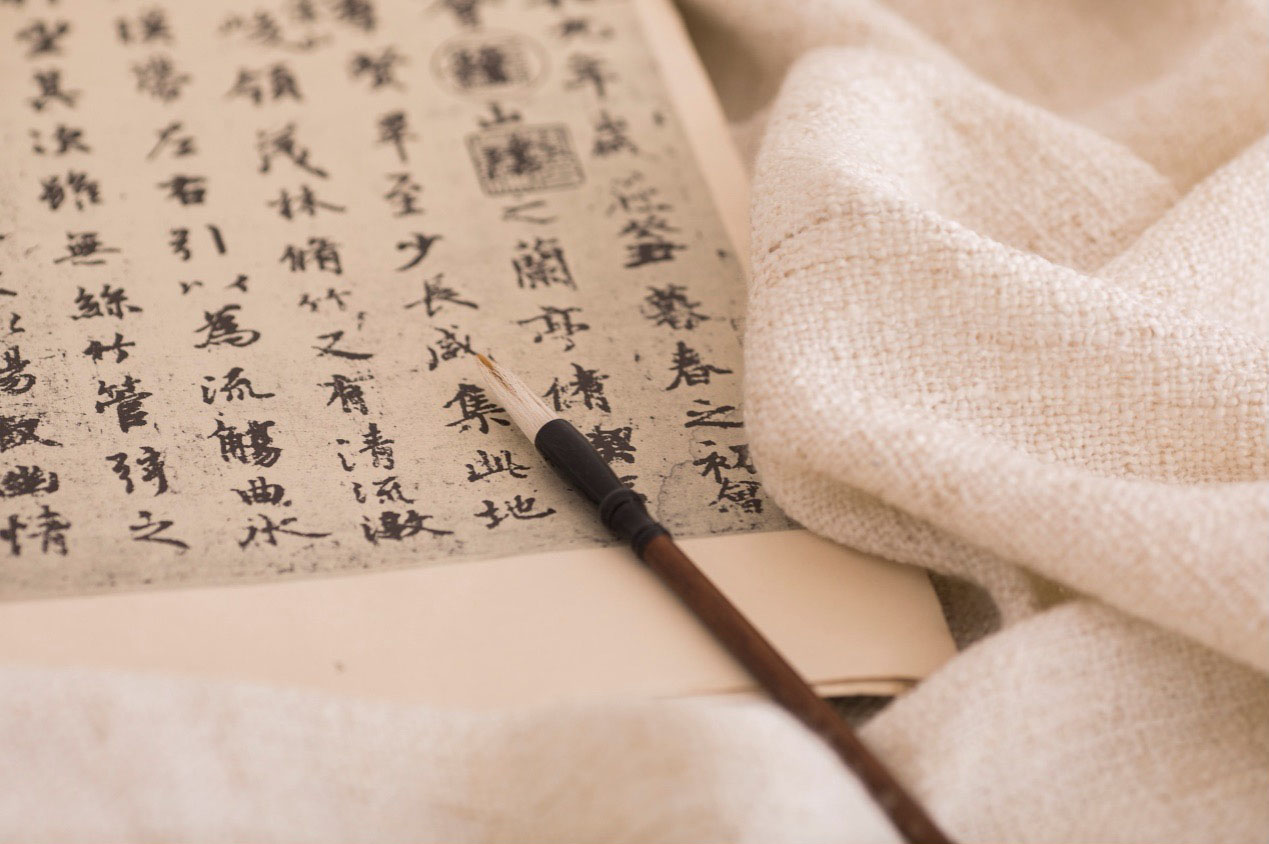

The bulk of Chinese literature and Chinese historiography was produced by the scholar-officials for their own reading. It was not available to the illiterate peasants and did not accurately reflect the values, beliefs, and feelings of the masses (Ruhlman, 1964). It has therefore been suggested that popular novels (such as the Four Classics) probably reflect the values, beliefs, and attitudes of the common people of China more accurately, albeit indirectly. The universally recognized Four Classics of Chinese literature are: Outlaws of the Marsh (also known as Water Margin) (Shi, ca.14th century), Romance of the Three Kingdoms (Luo, ca.14th century), Journey to the West (Wu, ca.16th century) and Dream of the Red Chamber (Cao, ca.18th century). They were written between the fourteenth and sixteenth centuries. The story lines in these novels are well-known to many people as they have featured in the production of countless plays, operas, cartoons, manga, artwork, toys, movies, television dramas, and video games for the past four to six hundred years. In a search for modern ethical insights in the Four Classics, it was concluded that the Romance of the Three Kingdoms is an encyclopedia of military and political ethics, Outlaws of the Marsh is an encyclopedia of daily-life ethics, Journey to the West is an encyclopedia of comparative ethics, and Dream of the Red Chamber is an encyclopedia of feudal family ethics (Lei, 2000).

Literature and Culture of the Ordinary People

On a more general note, literature has been referred to as a source of data which is not only observable but can also be subjected to systematic analysis and quantitative expression (Lindauer, 1984). The literature available to the peasant stratum of society and those not educated in a scholarly fashion, such as merchants and women, was originally presented orally and transmitted by storytellers and theatrical troupes that traveled from place to place. Stories that remained popular were passed from generation to generation, during which process they underwent changes that reflected the social, economic, and political mores of the times. Hence, the stories that were eventually recorded as popular novels could not realistically be credited to any single author.

Novels are said to stand at the intersection where social history meets the human soul (Feuerwerker, 1959). The attraction and popularity of the Four Classics lies in the fact that they drew upon a vast body of popular religious beliefs and commonly held knowledge about divination and magic, which was then woven into convoluted plots involving highly believable speculations about the ways of Heaven and Hell (Ruhlman, 1964). Jung (1954) referred to such literary works as artistic creations with a grand sense of vision and suggested that works of this genre had probably drawn on the authors' unconscious mind to the extent that their content appeared to have come from primordial times, was luxuriant with meaning, and challenged people's values.

In China, it was not until the twentieth century that novels and dramas began to be considered as literature, yet they are probably the only available source of historical information regarding the values, attitudes, and motivations of ordinary Chinese people (Ruhlman, 1964).

In Redfield's (1956) paradigm, the philosophical foundation of the Chinese personality can be likened to an exploration of the great tradition. In the following articles, the story lines, themes, and main characters of the Four Classics are examined in order to reveal the values, beliefs, and causal attributions of the Chinese people. This effort can be likened to discovering the little tradition in Redfield's paradigm. It would also be interesting to explore the convergence and divergence of these two traditions.

Major References

1、Jung, C. (1954). The collected works of C. G. Jung: Vol. 15. Spirit in man, art, and literature. Edited and translated by G. Adler & R. F. C. Hull. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

2、Redfield, R. (1956). Peasant society and culture: An anthropological approach to civilization. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

3、Feuerwerker, Y. T. M. (1959). The Chinese novel. In W. T. De Bary (Ed.), Approaches to the oriental classics; Asian literature and thought in general education. New York: Columbia University Press.

4、Ruhlmann, R. (1964). Traditional heroes in Chinese popular fiction. In A. F. Wright (Ed.), Confucianism and Chinese civilization (pp. 122-157). Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

5、Lindauer, M. S. (1984). Psychology and literature: An empirical perspective. In M. H. Bernstein (Ed.), Psychology and its allied disciplines (pp. 113-154). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

6、雷希(2000)。〈中國四大古典文學名著的現代倫理啟示〉。《雲南師範大學學報》,32, 3,48-52。

All articles/videos are prohibited from reproducing without the permission of the copyright holder.

Welcome to leave a message:

Please Sign In/Sign Up as a member and leave a message